MNSIT

From (Géron, 2023):

In this chapter we will be using the MNIST dataset, which is a set of 70,000 small images of digits handwritten by high school students and employees of the US Census Bureau. Each image is labeled with the digit it represents. This set has been studied so much that it is often called the “hello world” of machine learning: whenever people come up with a new classification algorithm they are curious to see how it will perform on MNIST, and anyone who learns machine learning tackles this dataset sooner or later.

The following code fetches the MNIST dataset from OpenML.org:

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_openml

mnist = fetch_openml('mnist_784', as_frame=False)Let’s look at these arrays:

>>>X, y = mnist.data, mnist.target

>>>X

]

X, y = mnist.data, mnist.target

X

array([[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

...,

[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.]])

>>>X.shape

(70000, 784)

>>>y

array(['5', '0', '4', ..., '4', '5', '6'], dtype=object)

>>>y.shape

(70000,)There are 70,000 images, and each image has 784 features. This is because each image is 28

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def plot_digit(image_data):

image = image_data.reshape(28, 28)

plt.imshow(image, cmap="binary")

plt.axis("off")

some_digit = X[0]

plot_digit(some_digit)

save_fig("some_digit_plot") # extra code

plt.show()

Example of an MNIST image

>>>y[0]

'5'You should always create a test set and set it aside before inspecting the data closely. The MNIST dataset returned by fetch_openml() is actually already split into a training set (the first 60,000 images) and a test set (the last 10,000 images):

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = X[:60000], X[60000:], y[:60000], y[60000:]The training set is already shuffled for us, which is good because this guarantees that all cross-validation folds will be similar (we don’t want one fold to be missing some digits).

Training a Binary Classifier

Let’s simplify the problem for now and only try to identify one digit - for example, the number 5. This “5-detector” will be an example of a binary classifier, capable of distinguishing between just two classes, 5 and non-5. First we’ll create the target vectors for this classification task:

y_train_5 = (y_train == '5') # True for all 5s, False for all other digits

y_test_5 = (y_test == '5')Now let’s pick a classifier and train it. A good place to start is with a stochastic gradient descent (SGD, or stochastic GD) classifier, using Scikit-Learn’s SGDClassifier class.

This classifier is capable of handling very large datasets efficiently. This is in part because SGD deals with training instances independently, one at a time, which also makes SGD well suited for online learning, as you will see later. Let’s create an SGDClassifier and train it on the whole training set:

from sklearn.linear_model import SGDClassifier

sgd_clf = SGDClassifier(random_state=42)

sgd_clf.fit(X_train, y_train_5)Now we can use it to detect images of the number 5:

>>> sgd_clf.predict([some_digit])

array([ True])The classifier guesses that this image represents a 5 (True). Looks like it guessed right in this particular case!

Performance Measures

Evaluating a classifier is often significantly trickier than evaluating a regressor, so we will spend a large part of this chapter on this topic.

Measuring Accuracy Using Cross-Validation

A good way to evaluate a model is to use cross-validation. Let’s use the cross_val_score() function to evaluate our SGDClassifier model, using k-fold cross-validation with three folds. Remember that k-fold cross-validation means splitting the training set into folds (in this case, three), then training the model k times, holding out a different fold each time for evaluation:

>>> from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

>>> cross_val_score(sgd_clf, X_train, y_train_5, cv=3, scoring="accuracy")

array([0.95035, 0.96035, 0.9604 ])This looks amazing, doesn’t it? Well, before you get too excited, This is simply because only about 10% of the images are 5s, so if you always guess that an image is not a 5, you will be right about 90% of the time.

This demonstrates why accuracy is generally not the preferred performance measure for classifiers, especially when you are dealing with skewed datasets (i.e., when some classes are much more frequent than others).

Confusion Matrices

A much better way to evaluate the performance of a classifier is to look at the confusion matrix (CM).

The general idea of a confusion matrix is to count the number of times instances of class A are classified as class B, for all A/B pairs. For example,

to know the number of times the classifier confused images of 8s with 0s, you would look at row #8, column #0 of the confusion matrix.

To compute the confusion matrix, you first need to have a set of predictions so that they can be compared to the actual targets.

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_predict

y_train_pred = cross_val_predict(sgd_clf, X_train, y_train_5, cv=3)Just like the cross_val_score() function, cross_val_predict() performs k-fold cross-validation, but instead of returning the evaluation scores, it returns the predictions made on each test fold.

Now you are ready to get the confusion matrix using the confusion_matrix() function. Just pass it the target classes (y_train_5) and the predicted classes (y_train_pred):

>>>from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix

>>>cm = confusion_matrix(y_train_5, y_train_pred)

>>>cm

array([[53892, 687], [ 1891, 3530]])Each row in a confusion matrix represents an actual class, while each column represents a predicted class. The first row of this matrix considers non-5 images (the negative class): 53,892 of them were correctly classified as non-5s (they are called true negatives), while the remaining 687 were wrongly classified as 5s (false positives, also called type I errors). The second row considers the images of 5s (the positive class): 1,891 were wrongly classified as non-5s (false negatives, also called type II errors), while the remaining 3,530 were correctly classified as 5s (true positives).

A perfect classifier would only have true positives and true negatives, so its confusion matrix would have nonzero values only on its main diagonal (top left to bottom right).

The confusion matrix gives you a lot of information, but sometimes you may prefer a more concise metric. An interesting one to look at is the accuracy of the positive predictions; this is called the precision of the classifier:

:

where

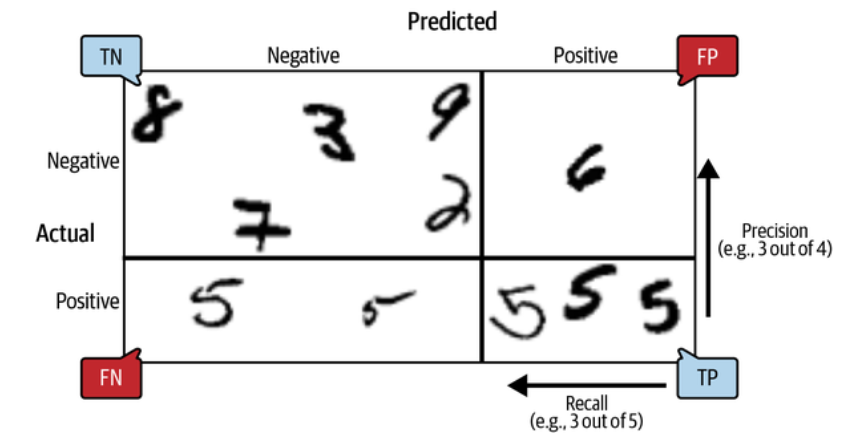

If you are confused about the confusion matrix, the following figure may help:

An illustrated confusion matrix showing examples of true negatives (top left), false positives (top right), false negatives (lower left), and true positives (lower right). (Géron, 2023).

Precision and Recall

Scikit-Learn provides several functions to compute classifier metrics, including precision and recall:

>>>from sklearn.metrics import precision_score, recall_score

>>>precision_score(y_train_5, y_train_pred) # == 3530 / (687 + 3530)

0.8370879772350012

>>>recall_score(y_train_5, y_train_pred) # == 3530 / (1891 + 3530)

0.6511713705958311Now our 5-detector does not look as shiny as it did when we looked at its accuracy. When it claims an image represents a 5, it is correct only 83.7% of the time. Moreover, it only detects 65.1% of the 5s. It is often convenient to combine precision and recall into a single metric called the

Whereas the regular mean treats all values equally, the harmonic mean gives much more weight to low values. As a result, the classifier will only get a high

To compute the f1_score() function:

>>>from sklearn.metrics import f1_score

>>>f1_score(y_train_5, y_train_pred)

0.7325171197343846The

Unfortunately, you can’t have it both ways: increasing precision reduces recall, and vice versa. This is called the precision/recall trade-off.

The Precision/Recall Trade-off

To understand this trade-off, let’s look at how the SGDClassifier makes its classification decisions. For each instance, it computes a score based on a decision function. If that score is greater than a threshold, it assigns the instance to the positive class; Otherwise it assigns it to the negative class.

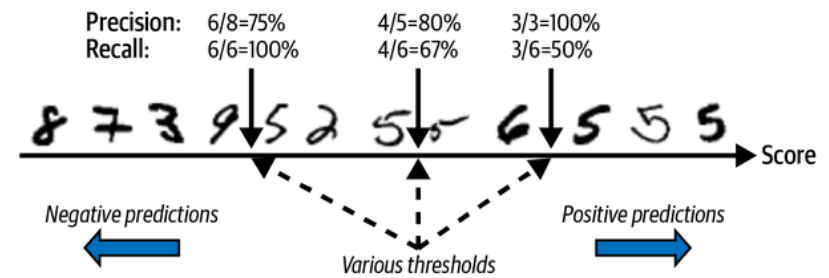

The following figure shows a few digits positioned from the lowest score on the left to the highest score on the right.

The precision/recall trade-off: images are ranked by their classifier score, and those above the chosen decision threshold are considered positive; the higher the threshold, the lower the recall, but (in general) the higher the precision.

Suppose the decision threshold is positioned at the central arrow (between the two 5s): you will find 4 true positives (actual 5s) on the right of that threshold, and 1 false positive (actually a 6). Therefore, with that threshold, the precision is 80% (4 out of 5). But out of 6 actual 5s, the classifier only detects 4, so the recall is 67% (4 out of 6). If you raise the threshold (move it to the arrow on the right), the false positive (the 6) becomes a true negative, thereby increasing the precision (up to 100% in this case), but one true positive becomes a false negative, decreasing recall down to 50%. Conversely, lowering the threshold increases recall and reduces precision.

Scikit-Learn does not let you set the threshold directly, but it does give you access to the decision scores that it uses to make predictions. Instead of calling the classifier’s predict() method, you can call its decision_function() method, which returns a score for each instance, and then use any threshold you want to make predictions based on those scores:

>>>y_scores = sgd_clf.decision_function([some_digit])

>>>y_scores

array([2164.22030239])

>>>threshold = 0

>>>y_some_digit_pred = (y_scores > threshold)

array([ True])The SGDClassifier uses a threshold equal to 0, so the preceding code returns the same result as the predict() method (i.e., True). Let’s raise the threshold:

>>> threshold = 3000

>>> y_some_digit_pred = (y_scores > threshold)

>>> y_some_digit_pred

array([False])This confirms that raising the threshold decreases recall. The image actually represents a 5, and the classifier detects it when the threshold is 0, but it misses it when the threshold is increased to 3,000.

How do you decide which threshold to use? First, use the cross_val_predict() function to get the scores of all instances in the training set, but this time specify that you want to return decision scores instead of predictions:

y_scores = cross_val_predict(sgd_clf, X_train, y_train_5, cv=3,

method="decision_function")With these scores, use the precision_recall_curve() function to compute precision and recall for all possible thresholds (the function adds a last precision of 0 and a last recall of 1, corresponding to an infinite threshold):

from sklearn.metrics import precision_recall_curve

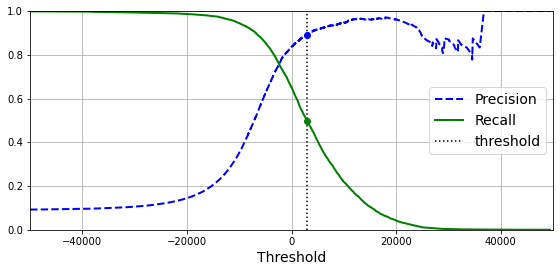

precisions, recalls, thresholds = precision_recall_curve(y_train_5, y_scores)Finally, use Matplotlib to plot precision and recall as functions of the threshold value. Let’s show the threshold of 3,000 we selected:

plt.plot(thresholds, precisions[:-1], "b--", label="Precision", linewidth=2)

plt.plot(thresholds, recalls[:-1], "g-", label="Recall", linewidth=2)

plt.vlines(threshold, 0, 1.0, "k", "dotted", label="threshold")

[...] # beautify the figure: add grid, legend, axis, labels, and circles

plt.show()

Precision and recall versus the decision threshold.

At this threshold value, precision is near 90% and recall is around 50%.

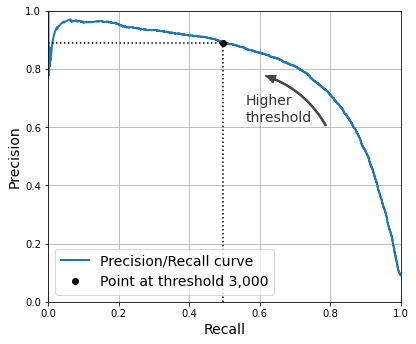

Another way to select a good precision/recall trade-off is to plot precision directly against recall, as shown in the following figure (the same threshold is shown):

Precision versus recall

You can see that precision really starts to fall sharply at around 80% recall. You will probably want to select a precision/recall trade-off just before that drop - for example, at around 60% recall. But of course, the choice depends on your project.

Suppose you decide to aim for 90% precision. For this, you can use the NumPy array’s argmax() method. This returns the first index of the maximum value, which in this case means the first True value:

>>>idx_for_90_precision = (precisions >= 0.90).argmax()

>>>threshold_for_90_precision = >>>thresholds[idx_for_90_precision]

3370.0194991439557

>>>y_train_pred_90 = (y_scores >= threshold_for_90_precision)

>>>precision_score(y_train_5, y_train_pred_90)

0.9000345901072293

>>>recall_at_90_precision = recall_score(y_train_5, y_train_pred_90)

>>>recall_at_90_precision

0.4799852425751706As you can see, it is fairly easy to create a classifier with virtually any precision you want: just set a high enough threshold, and you’re done. But wait, not so fast–a high-precision classifier is not very useful if its recall is too low! For many applications, 48% recall wouldn’t be great at all.

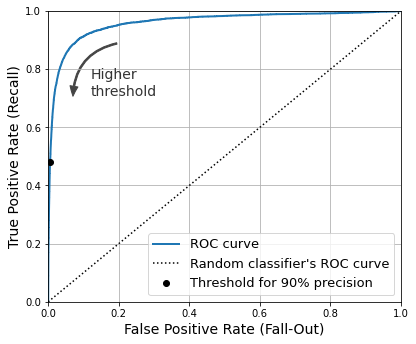

The ROC Curve

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve is another common tool used with binary classifiers. It is very similar to the precision/recall curve, but instead of plotting precision versus recall, the ROC curve plots the true positive rate (another name for recall) against the false positive rate (FPR). The FPR (also called the fall-out) is the ratio of negative instances that are incorrectly classified as positive.

To plot the ROC curve, you first use the roc_curve() function to compute the TPR and FPR for various threshold values:

from sklearn.metrics import roc_curve

fpr, tpr, thresholds = roc_curve(y_train_5, y_scores)Then you can plot the FPR against the TPR using Matplotlib:

idx_for_threshold_at_90 = (thresholds <= threshold_for_90_precision).argmax()

tpr_90, fpr_90 = tpr[idx_for_threshold_at_90], fpr[idx_for_threshold_at_90]

[...]

plt.show()

A ROC curve plotting the false positive rate against the true positive rate for all possible thresholds; the black circle highlights the chosen ratio (at 90% precision and 48% recall)

Once again there is a trade-off: the higher the recall (TPR), the more false positives (FPR) the classifier produces. The dotted line represents the ROC curve of a purely random classifier; a good classifier stays as far away from that line as possible (toward the top-left corner).

One way to compare classifiers is to measure the area under the curve (AUC). A perfect classifier will have a ROC AUC equal to 1, whereas a purely random classifier will have a ROC AUC equal to 0.5. Scikit-Learn provides a function to estimate the ROC AUC:

>>>from sklearn.metrics import roc_auc_score

>>>roc_auc_score(y_train_5, y_scores)

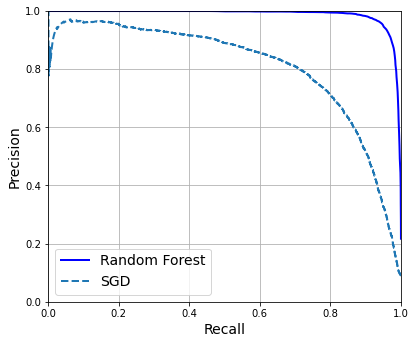

0.9604938554008616Let’s now create a RandomForestClassifier, whose PR curve and F score we can compare to those of the SGDClassifier:

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

forest_clf = RandomForestClassifier(random_state=42)The precision_recall_curve() function expects labels and scores for each instance, so we need to train the random forest classifier and make it assign a score to each instance. But the RandomForestClassifier class does not have a decision_function() method, due to the way it works. Luckily, it has a predict_proba() method that returns class probabilities for each instance, and we can just use the probability of the positive class as a score, so it will work fine. We can call the cross_val_predict() function to train the RandomForestClassifier using cross-validation and make it predict class probabilities for every image as follows:

y_probas_forest = cross_val_predict(forest_clf, X_train, y_train_5, cv=3,

method="predict_proba")Let’s look at the class probabilities for the first two images in the training set:

>>>y_probas_forest[:2]

array([[0.11, 0.89],

[0.99, 0.01]])The model predicts that the first image is positive with 89% probability, and it predicts that the second image is negative with 99% probability. Since each image is either positive or negative, the probabilities in each row add up to 100%.

The second column contains the estimated probabilities for the positive class, so let’s pass them to the precision_recall_curve() function:

y_scores_forest = y_probas_forest[:, 1]

precisions_forest, recalls_forest, thresholds_forest = precision_recall_curve(

y_train_5, y_scores_forest)Now we’re ready to plot the PR curve. It is useful to plot the first PR curve as well to see how they compare:

plt.plot(recalls_forest, precisions_forest, "b-", linewidth=2,

label="Random Forest")

plt.plot(recalls, precisions, "--", linewidth=2, label="SGD")

[...]

plt.show()

Comparing PR curves: the random forest classifier is superior to the SGD classifier because its PR curve is much closer to the top-right corner, and it has a greater AUC.

As you can see in the figure, the RandomForestClassifier’s PR curve looks much better than the SGDClassifier’s: it comes much closer to the top-right corner. Its

>>>y_train_pred_forest = y_probas_forest[:, 1] >= 0.5 # positive proba ≥ 50%

>>>f1_score(y_train_5, y_train_pred_forest)

0.9274509803921569

>>>roc_auc_score(y_train_5, y_scores_forest)

0.9983436731328145Multiclass Classification

Whereas binary classifiers distinguish between two classes, multiclass classifiers (also called multinomial classifiers) can distinguish between more than two classes.

Some Scikit-Learn classifiers (e.g., LogisticRegression, RandomForestClassifier, and GaussianNB) are capable of handling multiple classes natively. Others are strictly binary classifiers (e.g., SGDClassifier and SVC). However, there are various strategies that you can use to perform multiclass classification with multiple binary classifiers.

One way to create a system that can classify the digit images into 10 classes (from 0 to 9) is to train 10 binary classifiers, one for each digit (a 0-detector, a 1-detector, a 2-detector, and so on). Then when you want to classify an image, you get the decision score from each classifier for that image and you select the class whose classifier outputs the highest score. This is called the one-versus-the-rest (OvR) strategy, or sometimes one-versus-all (OvA).

Another strategy is to train a binary classifier for every pair of digits: one to distinguish 0s and 1s, another to distinguish 0s and 2s, another for 1s and 2s, and so on. This is called the one-versus-one (OvO) strategy. If there are

Some algorithms (such as support vector machine classifiers) scale poorly with the size of the training set. For these algorithms OvO is preferred because it is faster to train many classifiers on small training sets than to train few classifiers on large training sets. For most binary classification algorithms, however, OvR is preferred.

Scikit-Learn detects when you try to use a binary classification algorithm for a multiclass classification task, and it automatically runs OvR or OvO, depending on the algorithm. Let’s try this with a support vector machine classifier using the sklearn.svm.SVC class. We’ll only train on the first 2,000 images, or else it will take a very long time:

from sklearn.svm import SVC

svm_clf = SVC(random_state=42)

svm_clf.fit(X_train[:2000], y_train[:2000]) # y_train, not y_train_5Since there are 10 classes (i.e., more than 2), Scikit-Learn used the OvO strategy and trained 45 binary classifiers. Now let’s make a prediction on an image:

>>> svm_clf.predict([some_digit])

array(['5'], dtype=object)That’s correct! This code actually made 45 predictions - one per pair of classes - and it selected the class that won the most duels. If you call the decision_function() method, you will see that it returns 10 scores per instance: one per class. Each class gets a score equal to the number of won duels plus or minus a small tweak (max

>>> some_digit_scores = svm_clf.decision_function([some_digit])

>>>some_digit_scores_ovo = svm_clf.decision_function([some_digit])

>>>some_digit_scores_ovo.round(2)

array([[ 3.79, 0.73, 6.06, 8.3 , -0.29, 9.3 , 1.75, 2.77, 7.21, 4.82]])The highest score is 9.3, and it’s indeed the one corresponding to class 5.

When a classifier is trained, it stores the list of target classes in its classes_ attribute, ordered by value. In the case of MNIST, the index of each class in the classes_ array conveniently matches the class itself (e.g., the class at index 5 happens to be class ‘5’), but in general you won’t be so lucky; you will need to look up the class label like this:

>>> svm_clf.classes_

array(['0', '1', '2', '3', '4', '5', '6', '7', '8', '9'], dtype=object)

>>> svm_clf.classes_[class_id]

'5'Error Analysis

If this were a real project, you’d explore data preparation options, try out multiple models, shortlist the best ones, fine-tune their hyperparameters using GridSearchCV, and automate as much as possible. Here, we will assume that you have found a promising model and you want to find ways to improve it. One way to do this is to analyze the types of errors it makes.

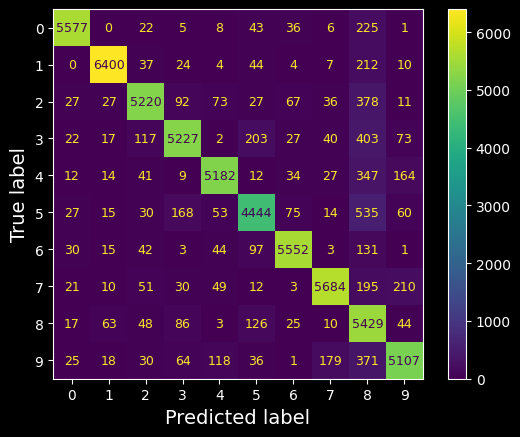

First, look at the confusion matrix. For this, you first need to make predictions using the cross_val_predict() function; then you can pass the labels and predictions to the confusion_matrix() function, just like you did earlier. However, since there are now 10 classes instead of 2, the confusion matrix will contain quite a lot of numbers, and it may be hard to read.

A colored diagram of the confusion matrix is much easier to analyze. To plot such a diagram, use the ConfusionMatrixDisplay.from_predictions() function like this:

from sklearn.metrics import ConfusionMatrixDisplay

y_train_pred = cross_val_predict(sgd_clf, X_train_scaled, y_train, cv=3)

plt.rc('font', size=9) # extra code – make the text smaller

ConfusionMatrixDisplay.from_predictions(y_train, y_train_pred)

plt.show()

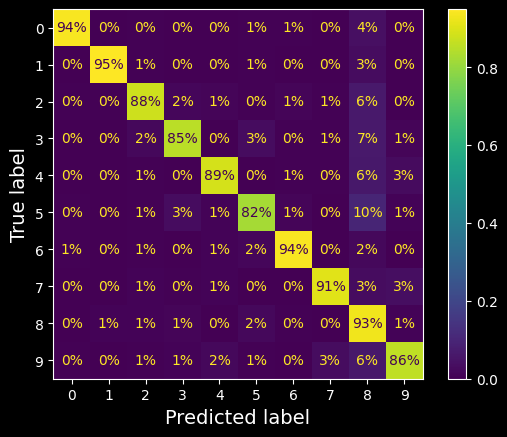

Confusion matrix

This confusion matrix looks pretty good: most images are on the main diagonal, which means that they were classified correctly. Notice that the cell on the diagonal in row #5 and column #5 looks slightly darker than the other digits. This could be because the model made more errors on 5s, or because there are fewer 5s in the dataset than the other digits. That’s why it’s important to normalize the confusion matrix by dividing each value by the total number of images in the corresponding (true) class (i.e., divide by the row’s sum). This can be done simply by setting normalize="true". We can also specify the values_format=".0%" argument to show percentages with no decimals.

plt.rc('font', size=10) # extra code

ConfusionMatrixDisplay.from_predictions(y_train, y_train_pred,

normalize="true", values_format=".0%")

plt.show()

The same CM normalized by row

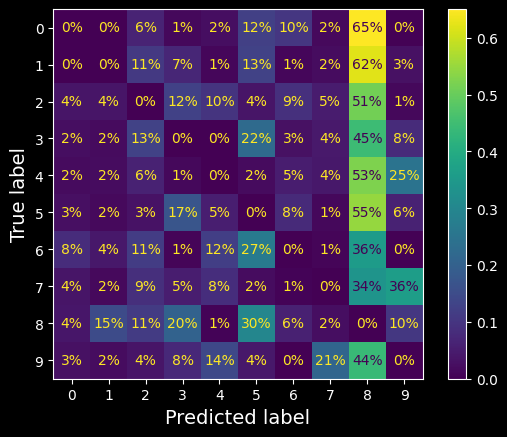

Now we can easily see that only 82% of the images of 5s were classified correctly. The most common error the model made with images of 5s was to misclassify them as 8s: this happened for 10% of all 5s. But only 2% of 8s got misclassified as 5s; confusion matrices are generally not symmetrical! If you look carefully, you will notice that many digits have been misclassified as 8s, but this is not immediately obvious from this diagram. If you want to make the errors stand out more, you can try putting zero weight on the correct predictions:

sample_weight = (y_train_pred != y_train)

plt.rc('font', size=10) # extra code

ConfusionMatrixDisplay.from_predictions(y_train, y_train_pred,

sample_weight=sample_weight,

normalize="true", values_format=".0%")

plt.show()

Confusion matrix with errors only, normalized by row.

The column for class 8 is now really bright, which confirms that many images got misclassified as 8s. In fact this is the most common misclassification for almost all classes. But be careful how you interpret the percentages in this diagram: remember that we’ve excluded the correct predictions. For example, the 36% in row #7, column #9 does not mean that 36% of all images of 7s were misclassified as 9s. It means that 36% of the errors the model made on images of 7s were misclassifications as 9s. In reality, only 3% of images of 7s were misclassified as 9s.

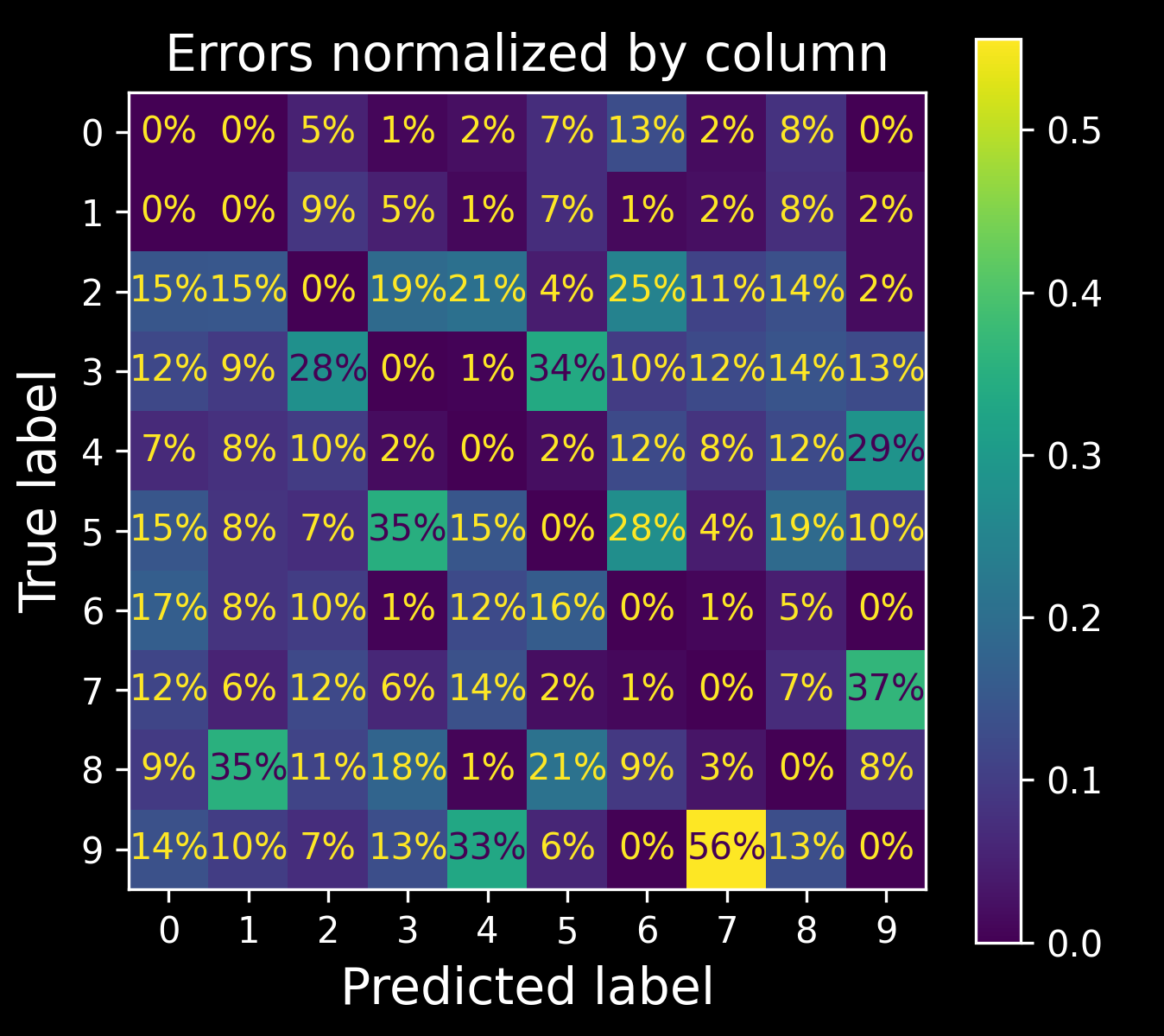

It is also possible to normalize the confusion matrix by column rather than by row: if you set normalize="pred", you get the following diagram:

Confusion matrix with errors only, normalized by column

For example, you can see that 56% of misclassified 7s are actually 9s.

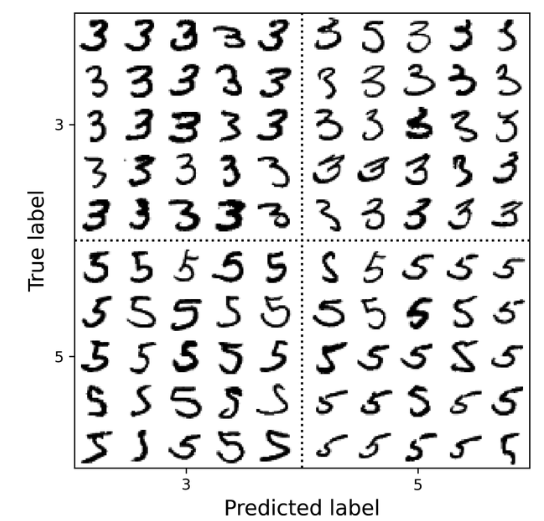

Analyzing the confusion matrix often gives you insights into ways to improve your classifier. Looking at these plots, it seems that your efforts should be spent on reducing the false 8s. For example, you could try to gather more training data for digits that look like 8s (but are not) so that the classifier can learn to distinguish them from real 8s. Analyzing individual errors can also be a good way to gain insights into what your classifier is doing and why it is failing. For example, let’s plot examples of 3s and 5s in a confusion matrix style:

cl_a, cl_b = '3', '5'

X_aa = X_train[(y_train == cl_a) & (y_train_pred == cl_a)]

X_ab = X_train[(y_train == cl_a) & (y_train_pred == cl_b)]

X_ba = X_train[(y_train == cl_b) & (y_train_pred == cl_a)]

X_bb = X_train[(y_train == cl_b) & (y_train_pred == cl_b)]

Some images of 3s and 5s organized like a confusion matrix.

As you can see, some of the digits that the classifier gets wrong (i.e., in the bottom-left and top-right blocks) are so badly written that even a human would have trouble classifying them. However, most misclassified images seem like obvious errors to us.

Recall that we used a simple SGDClassifier, which is just a linear model: all it does is assign a weight per class to each pixel, and when it sees a new image it just sums up the weighted pixel intensities to get a score for each class. Since 3s and 5s differ by only a few pixels, this model will easily confuse them.

The main difference between 3s and 5s is the position of the small line that joins the top line to the bottom arc. If you draw a 3 with the junction slightly shifted to the left, the classifier might classify it as a 5, and vice versa. In other words, this classifier is quite sensitive to image shifting and rotation. One way to reduce the 3/5 confusion is to preprocess the images to ensure that they are well centered and not too rotated. However, this may not be easy since it requires predicting the correct rotation of each image. A much simpler approach consists of augmenting the training set with slightly shifted and rotated variants of the training images. This will force the model to learn to be more tolerant to such variations. This is called data augmentation.

Multilabel Classification

Until now, each instance has always been assigned to just one class. But in some cases you may want your classifier to output multiple classes for each instance. Consider a face-recognition classifier: what should it do if it recognizes several people in the same picture? It should attach one tag per person it recognizes. Say the classifier has been trained to recognize three faces: Alice, Bob, and Charlie. Then when the classifier is shown a picture of Alice and Charlie, it should output [True, False, True] (meaning “Alice yes, Bob no, Charlie yes”). Such a classification system that outputs multiple binary tags is called a multilabel classification system.

We won’t go into face recognition just yet, but let’s look at a simpler example, just for illustration purposes:

import numpy as np

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

y_train_large = (y_train >= '7')

y_train_odd = (y_train.astype('int8') % 2 == 1)

y_multilabel = np.c_[y_train_large, y_train_odd]

knn_clf = KNeighborsClassifier()

knn_clf.fit(X_train, y_multilabel)This code creates a y_multilabel array containing two target labels for each digit image: the first indicates whether or not the digit is large (7, 8, or 9), and the second indicates whether or not it is odd. Then the code creates a KNeighborsClassifier instance, which supports multilabel classification (not all classifiers do), and trains this model using the multiple targets array. Now you can make a prediction, and notice that it outputs two labels:

>>> knn_clf.predict([some_digit])

array([[False, True]])And it gets it right! The digit 5 is indeed not large (False) and odd (True).

There are many ways to evaluate a multilabel classifier, and selecting the right metric really depends on your project. One approach is to measure the