From (Walpole et al., 2017):

Probability

Sample Space

In the study of statistics, we are concerned basically with presentation and interpretation of chance outcomes that occur in a planned study or scientific investigation. The statistician is often dealing with either numerical data, representing counts or measurements, or categorical data, which can be classified according to some criterion.

Definition:

The set of all possible outcomes of a statistical experiment is called the sample space and is represented by symbol

.

Each outcome in a sample space is called an element or a member of the sample space, or simply a sample point. If the sample space has a finite number of elements, we may list the members separated by commas and enclosed in braces. Thus, the sample space

where

Example:

Consider the experiment of tossing a die. If we are interested in the number that shows on the top face, the sample face is

If we are interested only in whether the number is even or odd, the sample space is simply

Events

For any given experiment, we may be interested in the occurrence of certain events rather than in the occurrence of a specific element in the sample space. For instance, we may be interested in the event

To each event we assign a collection of sample points, which constitute a subset of the sample space. That subset represents all of the elements for which the event is true.

Definition:

An event is subset of a sample space.

It is conceivable that an event may be a subset that includes the entire sample space

then

Various Set Operations

Definition:

The complement of an event

with respect to is the subset of all elements of that are not in . We denote the complement of by the symbol .

Example:

Let

be the event that a red card is selected from an ordinary deck of playing cards, and let be the entire deck. Then is the event that the card selected from the deck is not a red card but a black card.

Definition:

The Intersection of the two events

and , denoted by the symbol , is the event containing all elements that are common to and .

Definition:

Two events

and are mutually exclusive, or disjoint, if , that is, if and have no elements in common.

Definition:

The union of two events

and , denoted by the symbol , is the event containing all the elements that belong to or or both.

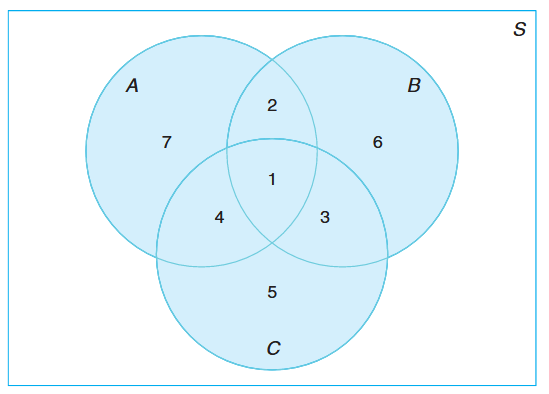

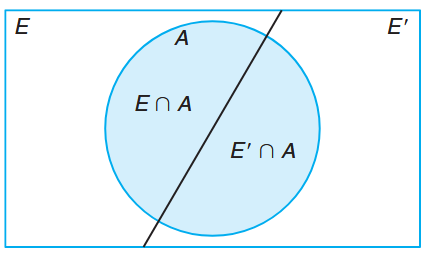

The relationship between events and the corresponding sample space can be illustrated graphically by means of Venn diagrams. In a Venn diagram we let the sample space a rectangle and represent events by circles drawn inside the rectangle.

Events represented by various regions. (Walpole et al., 2017).

Thus, in the figure above, we see that:

Some useful rules:

Counting Sample Points

One of the problems that the statistician must consider and attempt to evaluate is the element of chance associated with the occurrence of certain events when an experiment is performed. These problems belong in the field of probability. In many cases, we shall be able to solve a probability problem by counting the number of points in the sample space without actually listing each element. The fundamental principle of counting, often referred to as the multiplication rule, is the following:

Theorem:

If an operation can be performed in

ways, and if for each of these ways a second operation can be performed in ways, then the two operations can be performed together in ways.

This rule can be extended to cover any number of operations. Supposed for instance, that a customer wishes to buy a new cell phone and can choose from

Theorem:

If an operation can be performed in

ways, and if for each of these a second operation can be performed in ways, and for each of the first two a third operation can be performed in ways, and so forth, then the sequence of operations can be performed in ways.

Example:

How many even four-digit numbers can be formed from the digits

and if each digit can be used only once?

Solution:

Since the number must be even, we have onlychoices for the units position. However, for a four-digit number the thousands position cannot be . Hence, we consider the units position in two parts, or not . If the units position is (i.e., ), we have choices for the thousands position, for the hundreds position, and for the tens position. Therefore, in this case we have a total of even four-digit numbers. On the other hand, if the units position is not

(i.e., ), we have choices for the thousands position, for the hundreds position, for the tens position. Therefore, in this case we have a total of even four-digit numbers.

Since the above two cases are mutually exclusive, the total number of even four-digit numbers can be calculated as

Permutation

Definition:

A permutation is an arrangement of all or part of a set of objects.

Consider the three letters

Or simply:

Theorem:

The number of permutations of

objects is .

Now consider the number of permutations that are possible by taking two letters at a time from four. These would be

In general,

ways. We represent this product by the symbol

As a result, we have the following theorem:

Theorem:

The number of permutations of

distinct object taken at a time is

Example:

In one year, three awards (research, teaching, and service) will be given to a class of

graduate students in a statistics department. If each student can receive at most one award, how many possible selection are there? Solution:

Since the awards are distinguishable, it is a permutation problem. The total number of sample points is

Permutations that occur by arranging object in a circle are called circular permutations. Two circular permutations are not considered different unless corresponding objects in the two arrangements are preceded or followed by a different object as we proceed in a clockwise direction. For example, if

Theorem:

The number of permutations of

objects arranged in a circle is

So far we have considered permutations of distinct objects. That is, all the objects were completely different or distinguishable. Obviously, if the letters

Theorem:

The number of distinct permutations of

things of which are of one kind, of a second kind, , are of a -th kind is

Combination

In many problems, we are interested in the number of ways of selecting

Theorem:

The number of combinations of

distinct objects taken at a time is

Note:

Probability of an Event

Definition:

The probability of an event

is the sum of the weights of all sample points in . Therefore, Furthermore, if

is a sequence of mutually exclusive events, then

Example:

A coin is tossed twice. What is the probability that at least

head occurs?

Solution:

The space for this experiment isIf the coin is balanced, each of these outcomes is equally likely to occur. Therefore, we assign a probability of

to each sample point. Then , or . If represents the event of at least head occurring, then so

Some important rules:

Additive Rules

Often it is easiest to calculate the probability of some event from known probabilities of other events. This may well be true if the event in question can be represented as the union of two other events or as the complement of some event. Several important laws that frequently simplify the computation of probabilities follow. The first, called the additive rule, applies to union of events.

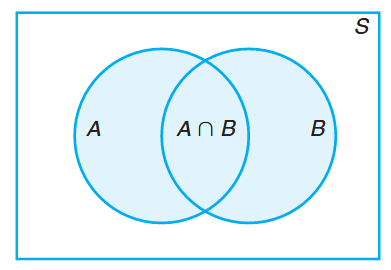

Theorem:

If

and are two events, then

Additive rule of probability. (Walpole et al., 2017).

Theorem:

If

and are disjoint, then

Which we can generalize:

Theorem:

If

are mutually exclusive (disjoint), then

Tip:

When in doubt, consider a Venn diagram.

Example:

How do employees commute to work? (defined as “use at least one a week”), given:

What are the probabilities for “not car”, “train or car”, “bike and not car”?

Solution:

Using the notationwe get:

For the third case, we know that:

So we can simple rearrange:

Conditional Probability, Independence, and the Product Rule

Conditional Probability

The probability of an event

Consider the event

This example illustrates that events may have different probabilities when considered relative to different sample spaces.

We can also write

Definition:

The conditional probability of

, given , denoted by , is defined by:

Another rule:

Independent Events

In the die tossing experiment we note that

Since the first card is replaced, our sample space for both the first and the second draw consists of

That is,

Although conditional probability allows for an alteration of the probability of an event in the light additional material, it also enables us to understand better the very important concept of independence or, in the present context, independent events.

Definition:

Two events

and are independent if and only if Assuming the existences of the conditional probabilities. Otherwise,

and are dependant.

Note:

The condition

implies that , and conversely.

The Multiplicative Rule

Multiplying the definition of the conditional probability above by

Theorem:

If in an experiment the events

and can both occur, then

Therefore, we can also write:

Example:

Suppose that we have a fuse box containing

fuses, of which are defective. If fuses are selected at random and removed from the box in succession without replacing the first, what is the probability that both fuses are defective?

Solution:

We shall letbe the event that the first fuse is defective and the event that second fuse is defective; then we interpret as the event that occurs and then occurs after has occurred. The probability of first removing a defective fuse is ; then the probability of removing a second defective fuse from the remaining is . Hence,

Bayesian Statistics

Bayesian statistics is a collection of tools that is used in a special form of statistical inference which applies in the analysis of experimental data in many practical situations in science and engineering. Bayes’ rule is one of the most important rules in probability theory.

Total Probability

Supposed that our sample space

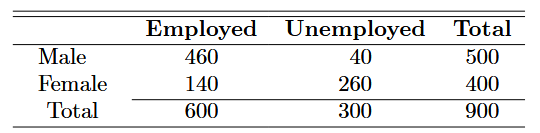

Categorization of the Adults in a Small Town.

One of these individuals is to be selected at random for a tour throughout the country to publicize the advantages of establishing new industries in the town. We shall be concerned with the following events:

Suppose that we are now given the additional information that

Venn diagram for the events

and . (Walpole et al., 2017).

Referring to the figure, we can write

From the table we can compute that:

and:

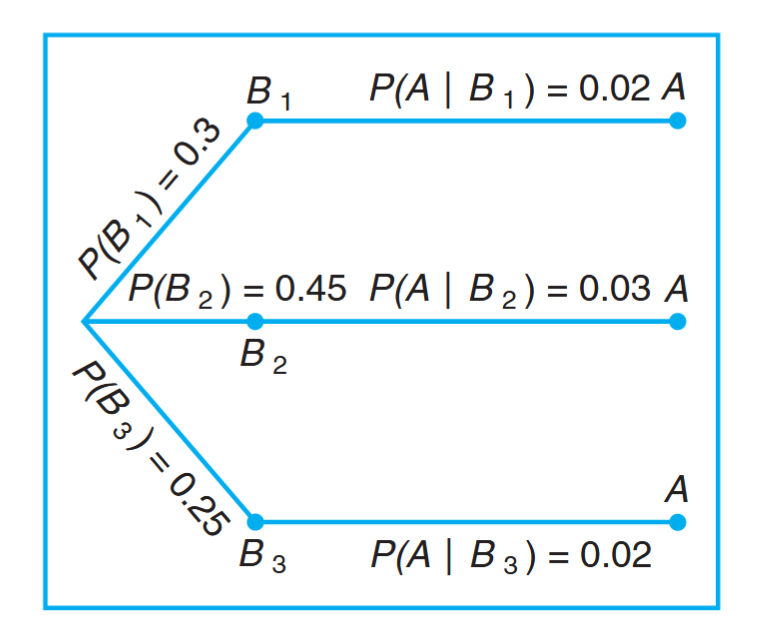

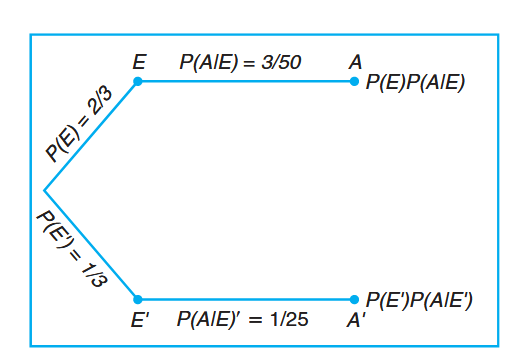

We can also display these probabilities by means of a tree diagram:

Tree diagram for the data above.

It follows that:

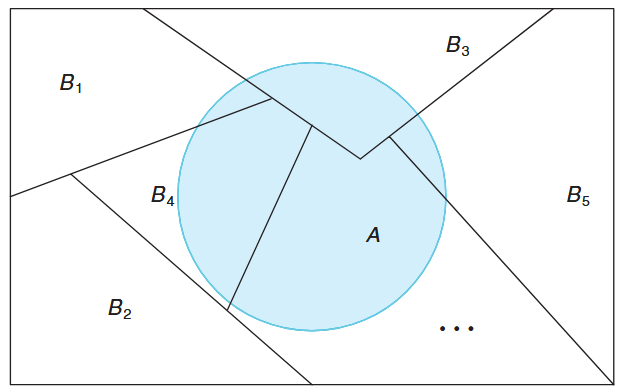

A generalization of the foregoing illustration to the case where the sample space is partitioned into

Theorem:

If the events

constitute a partition of the sample space such that for , then for any event of ,

Partitioning the sample space

. (Walpole et al., 2017).

Example:

In a certain assembly plant, three machines,

and , make , and , respectively, of the products. It is known from past experience that and of the products made by each machine, respectively, are defective. Now, suppose that a finished product is randomly selected. What is the probability that it is defective? Solutions:

Consider the following events:

- the product is defective - the product is made by machine , - the product is made by machine , - the product is made by machine Applying the rule of elimination, we can write

Tree diagram for the example above.

Referring to the tree diagram of the figure above, we find that the three branches give the probabilities

and hence

Bayes’ Rule

Instead of asking for

Theorem:

If the events

constitute a partition of the sample space such that for , then for any event in such that ,

Example:

A medical test has a

sensitivity (i.e., detects the disease in of people who have it) and specificity (i.e., does not detect the disease in of people who do not have it). If

of the population have this disease (a prevalence), what is the probability that a person who tests positive has the disease (this is called the “positive predictive value”)? Solution:

Let

- positive test result - disease Therefore, we know that:

So that:

We want to know what’s the probability of

knowing . Using Bayes’ rule:

Exercises

Question 1

Calculate:

Solution:

- Using the Various Set Operations:

- Using the Various Set Operations:

Question 2

The chance of a student to solve:

- question 1 correctly is

- question 3 correctly is

- both questions correctly is

Part a

What is the chance of a student to solve at least one question correctly?

Solution:

Let’s denote:

We know that:

Solving at least one question correctly corresponds to ”

Part b

What is the chance of a student to solve none of the questions correctly?

Solution:

Solving at none of the questions correctly corresponds to “not

Part c

What is the chance of a student to solve only one question correctly?

Solution:

Solving only one question correctly corresponds to ”

We know that

Substituting known values we can see that:

Doing the same for

Question 3

In how many ways can we choose two people with different nationalities, given out of a group of

Solution:

If there were only

Question 4

Out of

- With no limitation.

- If

Solution:

In the case where there is no limitation, we can simple calculate using a theorem:

In the second case, the problem is a bit more complicated. We can separate it to three different situations:

- None of special tenants are in the committee.

- The first special tenant is in the committee.

- The second special tenant is in the committee.

For the first situation, we simply use the same theorem again, but now we have

For the second situation, we now already know one of tenants in the committee, so we have

The third situation is exactly the same as the second one, so we have another

Summing all the different options, we get

Question 5

Consider a bag containing

Solution:

The basic formula is

Another thing we can try is to treat all the black balls as one group - just as a single ball. Doing that, we get

These permutations contain repeated elements (

Question 6

Drinking cups are produced in a

The probability that a deformed cup is properly painted is

Part a

What is the probability that a random cup produced is properly shaped but improperly painted?

Solution:

Let’s denote

We are given that:

We need to find

Probability tree for the given problem.

From the tree above, and from the the multiplication rule, we see that:

Part b

What is the probability that a cup is properly painted?

Solution:

Using the total probability rule:

Part c

If a cup is improperly painted, what is the probability it is properly shaped?

Solution:

We need to find