Random Sampling

The outcome of a statistical experiment may be recorded either as a numerical value or as a descriptive representation. For example, when a pair of dice is tossed and the total is the outcome of interest, we record a numerical value. However, if the students of a certain school are given blood tests and the type of blood is of interest, then a descriptive representation might be more useful. A person’s blood can be classified in 8 ways:

In this chapter, we focus on sampling from distributions or populations and study such important quantities as the sample mean and sample variance, which will be of vital importance in future chapters. In addition, we introduce the role that the sample mean and variance will play in statistical inference. The use of modern high-speed computers allows the scientist or engineer to greatly enhance their use of formal statistical inference with graphical techniques. Much of the time, formal inference appears quite dry and perhaps even abstract to the practitioner or to the manager who wishes to let statistical analysis be a guide to decision-making.

Populations and Samples

We begin by discussing the notions of populations and samples. Both are mentioned in a broad fashion in the introductory chapter, but more detail is needed here, particularly in the context of random variables.

Definition:

A population consists of the totality of the observations with which we are concerned. The number of observations in the population is called the size of the population.

Examples:

- The numbers on the cards in a deck, the heights of residents in a certain city, and the lengths of fish in a particular lake are examples of populations with finite size.

- The observations obtained by measuring the atmospheric pressure every day, from the past on into the future, or all measurements of the depth of a lake, from any conceivable position, are examples of populations whose sizes are infinite.

- Some finite populations are so large that in theory we assume them to be infinite (e.g., the population of lifetimes of a certain type of storage battery being manufactured for mass distribution).

Each observation in a population is a value of a random variable

- Inspecting items coming off an assembly line for defects: each observation is a value

$$

b(x; 1, p) = p^x q^{1-x}, \quad x = 0, 1 - In the blood-type experiment, the random variable

- The lives of storage batteries are values assumed by a continuous random variable, perhaps with a normal distribution.

When we refer to a “binomial population,” a “normal population,” or, in general, the “population

In statistical inference, we are interested in drawing conclusions about a population when it is impossible or impractical to observe the entire set of observations. For example, to determine the average length of life of a certain brand of light bulb, it would be impossible to test all such bulbs. Exorbitant costs can also be a prohibitive factor. Therefore, we depend on a subset of observations from the population to help us make inferences concerning that population. This brings us to the notion of sampling.

Definition:

A sample is a subset of a population.

If our inferences from the sample to the population are to be valid, we must obtain samples that are representative of the population. Any sampling procedure that produces inferences that consistently overestimate or consistently underestimate some characteristic of the population is said to be biased. To eliminate bias, it is desirable to choose a random sample: observations made independently and at random.

Suppose we select a random sample of size

Definition:

Let

be independent random variables, each having the same probability distribution . Then form a random sample of size from the population , with joint probability distribution

Example:

If we select

storage batteries from a manufacturing process and record the life of each battery, with the value of , the value of , etc., then are the values of the random sample . If the population of battery lives is normal, each has the same normal distribution as .

Some Important Statistics

Our main purpose in selecting random samples is to elicit information about unknown population parameters. For example, to estimate the proportion

Definition:

Any function of the random variables constituting a random sample is called a statistic.

Location Measures of a Sample: The Sample Mean, Median, and Mode

Let

-

Sample mean:

The statistic

-

Sample median:

The sample median is the middle value of the sample.

-

Sample mode:

The value of the sample that occurs most often.Example:

Suppose a data set consists of the following observations:

0.32,\ 0.53,\ 0.28,\ 0.37,\ 0.47,\ 0.43,\ 0.36,\ 0.42,\ 0.38,\ 0.43

>The sample mode is $0.43$, since it occurs more than any other value.

Variability Measures of a Sample: The Sample Variance, Standard Deviation, and Range

A measure of location or central tendency in a sample does not by itself give a clear indication of the nature of the sample. Thus, a measure of variability in the sample must also be considered.

The variability in a sample displays how the observations spread out from the average.

-

Sample variance:

The computed value for a given sample is denoted

Example:

A comparison of coffee prices at 4 randomly selected grocery stores in San Diego showed increases from the previous month of

Solution:

Sample mean:

Sample variance: -

An alternative formula for the sample variance is:

Theorem:

If

-

Sample standard deviation:

where

-

Sample range:

Example:

Find the variance of the data

, representing the number of trout caught by a random sample of 6 fishermen. Solution:

Calculating the sample mean, we get

We find that, , and . Hence, Sample standard deviation:

Sample range:

Sampling Distribution of Means

The first important sampling distribution to be considered is that of the mean

Hence, we conclude that

has a normal distribution with mean

and variance

If we are sampling from a population with unknown distribution, either finite or infinite, the sampling distribution of

The Central Limit Theorem

The Central Limit Theorem is one of the most important results in probability theory and statistics. It provides the theoretical foundation for many statistical procedures and explains why the normal distribution appears so frequently in nature.

Theorem:

The Central Limit Theorem states that if

is the mean of a random sample of size taken from a population with mean and finite variance , then the limiting form of the distribution of as

, is the standard normal distribution .

The normal approximation for

The sample size

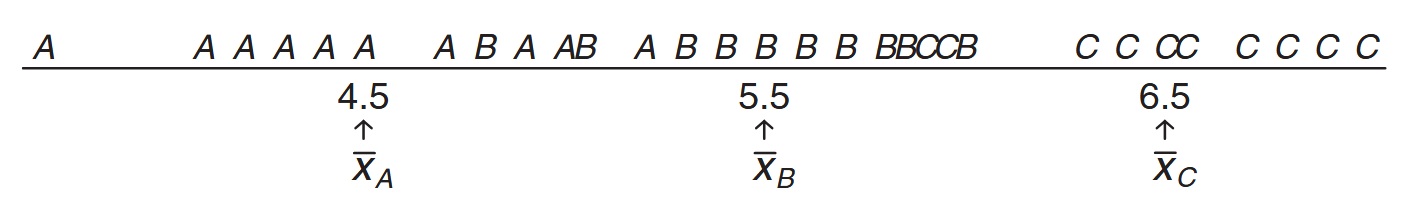

Illustration of the Central Limit Theorem (distribution of

for , moderate , and large ). (Walpole et al., 2017).

The figure shows how the distribution of

Example:

An electrical firm manufactures light bulbs that have a length of life that is approximately normally distributed, with mean equal to

hours and a standard deviation of hours. Find the probability that a random sample of bulbs will have an average life of less than hours. Solution:

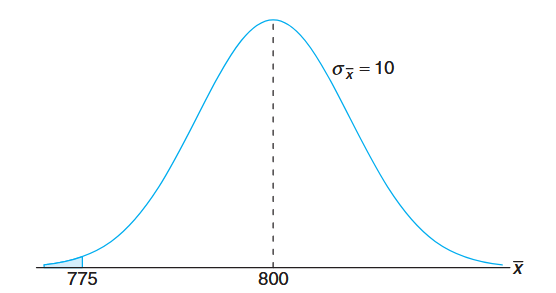

The sampling distribution ofwill be approximately normal, with and . The desired probability is given by the area of the shaded region in the following figure:

Corresponding to

, we find that and therefore

Inferences on the Population Mean

One very important application of the Central Limit Theorem is the determination of reasonable values of the population mean

Case Study: Automobile Parts

An important manufacturing process produces cylindrical component parts for the automotive industry. It is important that the process produce parts having a mean diameter of

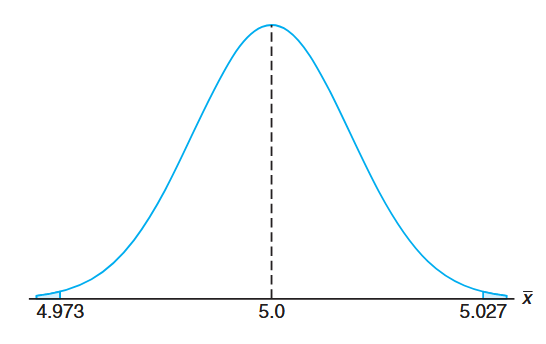

. The engineer involved conjectures that the population mean is . An experiment is conducted in which parts produced by the process are selected randomly and the diameter measured on each. It is known that the population standard deviation is . The experiment indicates a sample average diameter of . Does this sample information appear to support or refute the engineer’s conjecture? Solution:

This example reflects the kind of problem often posed and solved with hypothesis testing machinery introduced in future chapters. We will not use the formality associated with hypothesis testing here, but we will illustrate the principles and logic used.Whether the data support or refute the conjecture depends on the probability that data similar to those obtained in this experiment (

) can readily occur when in fact (See the following figure). In other words, how likely is it that one can obtain with if the population mean is ?

The probability that we choose to compute is given by

. In other words, if the mean is 5, what is the chance that will deviate by as much as ? P(|\overline{X} - 5| \geq 0.027) &= P(\overline{X} - 5 \geq 0.027) + P(\overline{X} - 5 \leq -0.027) \\ &= 2P\left(\frac{\overline{X} - 5}{0.1/\sqrt{100}} \geq 2.7\right) \end{aligned}$$ Here we are simply standardizing $\overline{X}$ according to the Central Limit Theorem. If the conjecture $\mu = 5.0$ is true, $\frac{\overline{X}-5}{0.1/\sqrt{100}}$ should follow $N(0, 1)$. Thus, $$2P\left(\frac{\overline{X} - 5}{0.1/\sqrt{100}} \geq 2.7\right) = 2P(Z \geq 2.7) = 2(0.0035) = 0.007.

Sampling Distribution of S²

In the preceding section we learned about the sampling distribution of

tends toward

If a random sample of size

By the addition and subtraction of the sample mean

Expanding this expression:

The cross-product term equals zero because

Dividing each term of the equality by

Now, it known that

is a chi-squared random variable with

Theorem:

If

is the variance of a random sample of size taken from a normal population having the variance , then the statistic has a chi-squared distribution with

degrees of freedom.

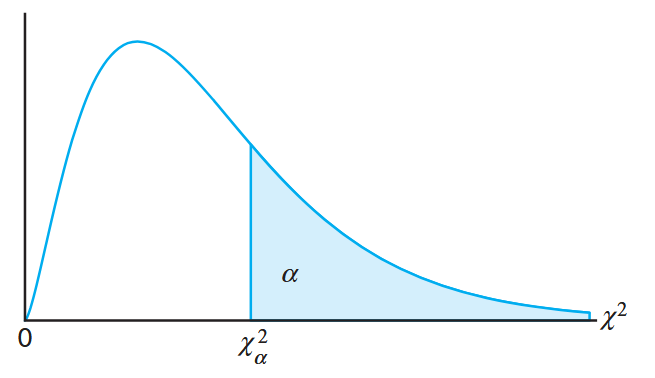

The values of the random variable

The probability that a random sample produces a

The chi-squared distribution. (Walpole et al., 2017).

There are tables that give values of

Exactly

Example:

A manufacturer of car batteries guarantees that the batteries will last, on average,

years with a standard deviation of year. If five of these batteries have lifetimes of , , , , and years, should the manufacturer still be convinced that the batteries have a standard deviation of year? Assume that the battery lifetime follows a normal distribution. Solution:

We first find the sample variance using the alternative formula:Then

is a value from a chi-squared distribution with

degrees of freedom. Since of the values with degrees of freedom fall between and , the computed value with is reasonable, and therefore the manufacturer has no reason to suspect that the standard deviation is other than year.

Degrees of Freedom as a Measure of Sample Information

It is known that

has a

has a

The reader can view the theorem as indicating that when

there is

In other words, there are

This concept of “losing” a degree of freedom when estimating parameters is fundamental to understanding why we use

t-Distribution

In The Central Limit Theorem, we discussed the utility of the Central Limit Theorem. Its applications revolve around inferences on a population mean or the difference between two population means. Use of the Central Limit Theorem and the normal distribution is certainly helpful in this context. However, it was assumed that the population standard deviation is known. This assumption may not be unreasonable in situations where the engineer is quite familiar with the system or process. However, in many experimental scenarios, knowledge of

since

In developing the sampling distribution of

where

has the standard normal distribution and

has a chi-squared distribution with

Theorem:

Let

be a standard normal random variable and a chi-squared random variable with degrees of freedom. If and are independent, then the distribution of the random variable , where is given by the density function

This is known as the t-distribution with

degrees of freedom.

From the foregoing and the theorem above we have the following corollary.

Corollary:

Let

be independent random variables that are all normal with mean and standard deviation . Let Then the random variable

has a t-distribution with

degrees of freedom.

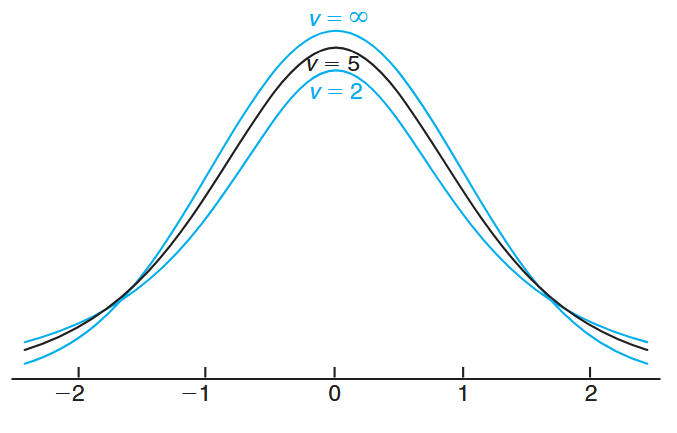

The probability distribution of

What Does the t-Distribution Look Like?

The distribution of

The t-distribution curves for

and . (Walpole et al., 2017).

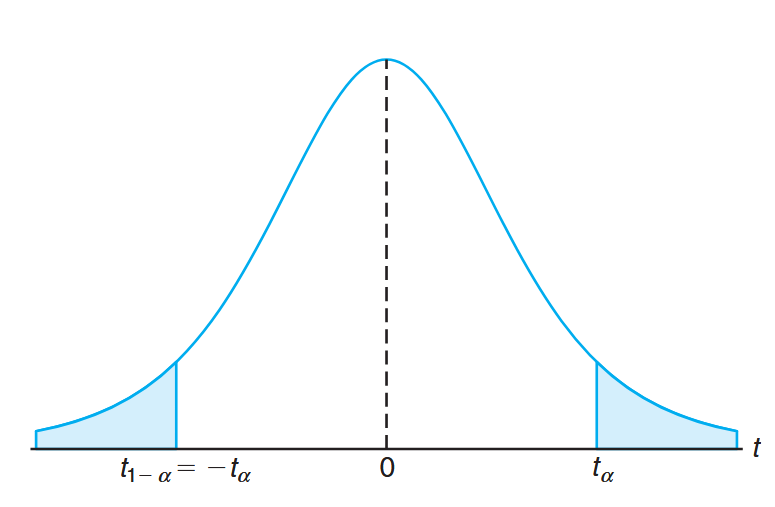

The percentage points of the t-distribution are usually given in a table.

It is customary to let

Symmetry property (about 0) of the t-distribution. (Walpole et al., 2017).

That is,

Example:

The t-value with

degrees of freedom that leaves an area of to the left, and therefore an area of to the right, is

Example:

Find

. Solution:

Sinceleaves an area of to the right, and leaves an area of to the left, we find a total area of between

and . Hence

Example:

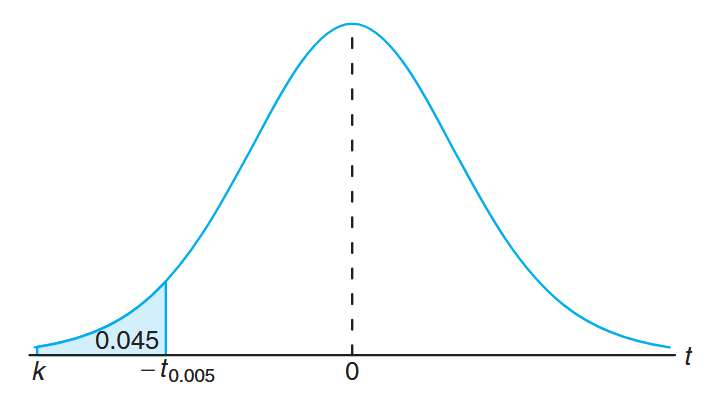

Find

such that for a random sample of size selected from a normal distribution and .

Solution:

From a t-distribution table we note thatcorresponds to when . Therefore, . Since in the original probability statement is to the left of , let . Then, from the figure, we have Hence, from the table with

, and

Exactly

Example:

A chemical engineer claims that the population mean yield of a certain batch process is

grams per milliliter of raw material. To check this claim he samples batches each month. If the computed t-value falls between and , he is satisfied with this claim. What conclusion should he draw from a sample that has a mean grams per milliliter and a sample standard deviation grams? Assume the distribution of yields to be approximately normal. Solution:

From a table we find thatfor degrees of freedom. Therefore, the engineer can be satisfied with his claim if a sample of batches yields a t-value between and . If , then a value well above

. The probability of obtaining a t-value, with , equal to or greater than is approximately . If , the value of computed from the sample is more reasonable. Hence, the engineer is likely to conclude that the process produces a better product than he thought.

What Is the t-Distribution Used For?

The t-distribution is used extensively in problems that deal with inference about the population mean (as illustrated in the example above) or in problems that involve comparative samples (i.e., in cases where one is trying to determine if means from two samples are significantly different).

Important Notes:

- The use of the t-distribution for the statistic

requires that be normal. - The use of the t-distribution and the sample size consideration do not relate to the Central Limit Theorem.

- The use of the standard normal distribution rather than

for merely implies that is a sufficiently good estimator of in this case. - In chapters that follow, the t-distribution finds extensive usage.

F-Distribution

We have motivated the t-distribution in part by its application to problems in which there is comparative sampling (i.e., a comparison between two sample means). For example, some of our examples in future chapters will take a more formal approach: a chemical engineer collects data on two catalysts, a biologist collects data on two growth media, or a chemist gathers data on two methods of coating material to inhibit corrosion. While it is of interest to let sample information shed light on two population means, it is often the case that a comparison of variability is equally important, if not more so. The F-distribution finds enormous application in comparing sample variances. Applications of the F-distribution are found in problems involving two or more samples.

The statistic

where

Theorem:

Let

and be two independent random variables having chi-squared distributions with and degrees of freedom, respectively. Then the distribution of the random variable is given by the density function

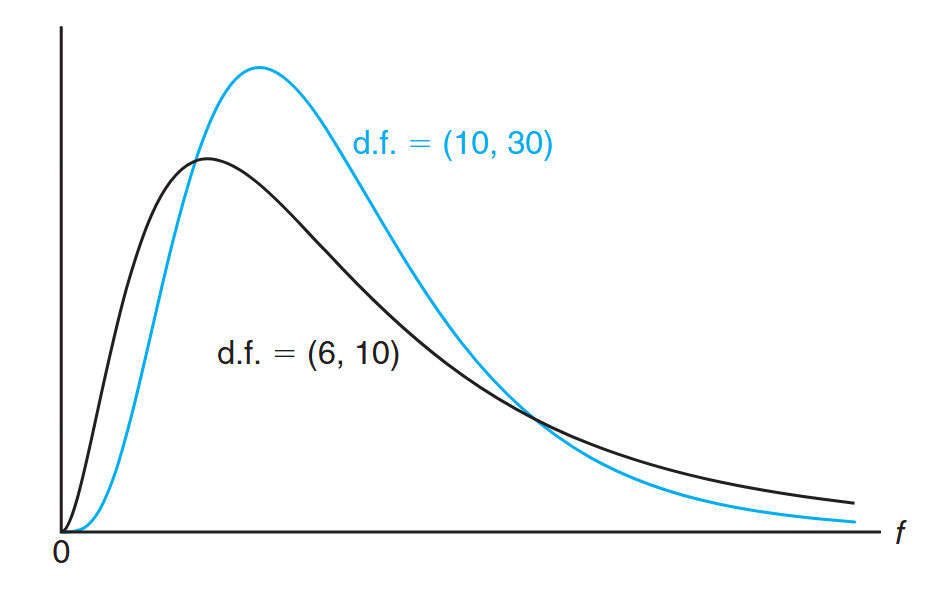

This is known as the F-distribution with

and degrees of freedom (d.f.).

We will make considerable use of the random variable

Typical F-distributions. (Walpole et al., 2017).

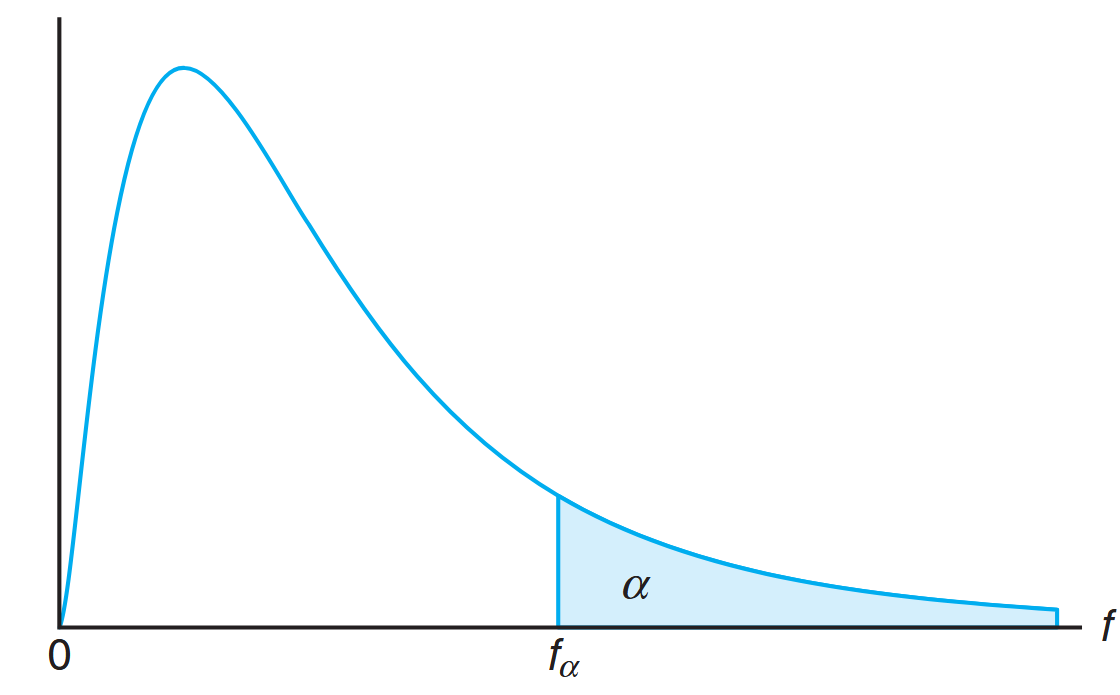

Let

Illustration of the

for the F-distribution. (Walpole et al., 2017).

Tables give values of

Theorem:

Writing

for with and degrees of freedom, we obtain

Thus, the f-value with

The F-Distribution with Two Sample Variances

Suppose that random samples of size

are random variables having chi-squared distributions with

Theorem:

If

and are the variances of independent random samples of size and taken from normal populations with variances and , respectively, then has an F-distribution with

and degrees of freedom.

What Is the F-Distribution Used For?

We answered this question, in part, at the beginning of this section. The F-distribution is used in two-sample situations to draw inferences about the population variances. This involves the application of the theorem above. However, the F-distribution can also be applied to many other types of problems involving sample variances. In fact, the F-distribution is called the variance ratio distribution.

As an illustration, consider a case in which two paints,

| Paint | Sample Mean | Sample Variance | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|

The problem centers around whether or not the sample averages

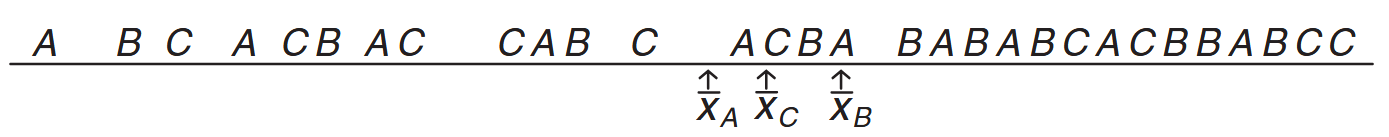

The notion of the important components of variability is best seen through some simple graphics. Consider the plot of raw data from samples

Data from three distinct samples. (Walpole et al., 2017).

It appears evident that the data came from distributions with different population means, although there is some overlap between the samples. An analysis that involves all of the data would attempt to determine if the variability between the sample averages and the variability within the samples could have occurred jointly if in fact the populations have a common mean. Notice that the key to this analysis centers around the following two sources of variability:

Two Sources of Variability:

- Variability within samples (between observations in distinct samples)

- Variability between samples (between sample averages)

Clearly, if the variability in (1) is considerably larger than that in (2), there will be considerable overlap in the sample data, a signal that the data could all have come from a common distribution. An example is found in the data set shown in the following figure:

Data that easily could have come from the same population. (Walpole et al., 2017).

On the other hand, it is very unlikely that data from distributions with a common mean could have variability between sample averages that is considerably larger than the variability within samples.

The sources of variability in (1) and (2) above generate important ratios of sample variances, and ratios are used in conjunction with the F-distribution. The general procedure involved is called analysis of variance. It is interesting that in the paint example described here, we are dealing with inferences on three population means, but two sources of variability are used. We will not supply details here, but in future chapters we make extensive use of analysis of variance, and, of course, the F-distribution plays an important role.

Key Applications of F-Distribution:

- Comparing population variances from two or more samples

- Analysis of variance (ANOVA) procedures

- Testing equality of multiple population means

- Quality control and experimental design

- The F-distribution is also known as the variance ratio distribution