from (Lynch & Park, 2017):

Motion planning is the problem of finding a robot motion from a start state to a goal state that avoids obstacles in the environment and satisfies other constraints, such as joint limits or torque limits. Motion planning is one of the most active subfields of robotics, and it is the subject of entire books. The purpose of this chapter is to provide a practical overview of a few common techniques, using robot arms and mobile robots as the primary example systems. The chapter begins with a brief overview of motion planning. This is followed by foundational material including configuration space obstacles and graph search. We conclude with summaries of several different planning methods.

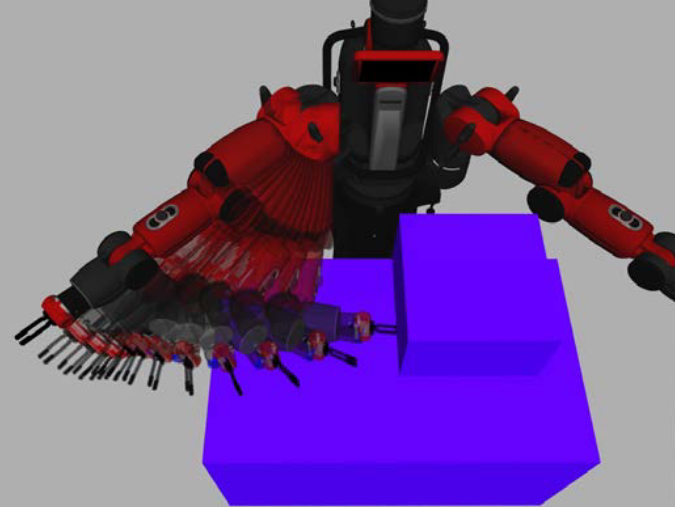

A robot arm executing an obstacle-avoiding motion plan. The motion plan was generated using MoveIt! and visualized using rviz in ROS (the Robot Operating System). (Lynch & Park, 2017).

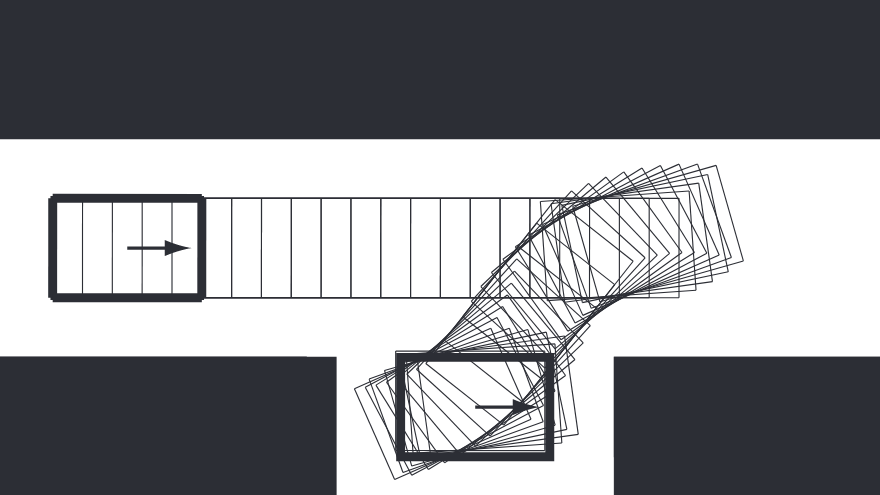

A car-like mobile robot executing parallel parking. (Lynch & Park, 2017).

Overview of Motion Planning

Definition:

Configuration space, or C-space for short, is a space where every point corresponds to a unique configuration

of the robot, and every configuration of the robot can be represented as a point in C-space.

For example, the configuration of a robot arm with

The control inputs available to drive the robot are written as an

The equations of motion of the robot are written

or, in integral form,

Types of Motion Planning Problems

Definition:

Given an initial state

and a desired final state , find a time and a set of controls such that the motion (LP10.2) satisfies and for all .

It is assumed that a feedback controller is available to ensure that the planned motion

Path Planning versus Motion Planning: The path planning problem is a subproblem of the general motion planning problem. Path planning is the purely geometric problem of finding a collision-free path

It is assumed that the path returned by the path planner can be time scaled to create a feasible trajectory. This problem is sometimes called the piano mover’s problem, emphasizing the focus on the geometry of cluttered spaces.

Control Inputs:

Online versus Offline: A motion planning problem requiring an immediate result, perhaps because obstacles appear, disappear, or move unpredictably, calls for a fast, online planner. If the environment is static then a slower offline planner may suffice.

Optimal versus Satisficing: In addition to reaching the goal state, we might want the motion plan to minimize (or approximately minimize) a cost

For example, minimizing with

Exact versus Approximate: We may be satisfied with a final state

With or Without Obstacles: The motion planning problem can be challenging even in the absence of obstacles, particularly if

Properties of Motion Planners

Planners must conform to the properties of the motion planning problem as outlined above. In addition, planners can be distinguished by the following properties.

Multiple-Query versus Single-Query Planning: If the robot is being asked to solve a number of motion planning problems in an unchanging environment, it may be worth spending the time building a data structure that accurately represents

“Anytime” Planning: An anytime planner is one that continues to look for better solutions after a first solution is found. The planner can be stopped at any time, for example when a specified time limit has passed, and the best solution returned.

Completeness: A motion planner is said to be complete if it is guaranteed to find a solution in finite time if one exists, and to report failure if there is no feasible motion plan. A planner is resolution complete if it is guaranteed to find a solution if one exists at the resolution of a discretized representation of the problem, such as the resolution of a grid representation of

Computational Complexity: The computational complexity refers to characterizations of the amount of time the planner takes to run or the amount of memory it requires. These are measured in terms of the description of the planning problem, such as the dimension of the C-space or the number of vertices in the representation of the robot and obstacles. For example, the time for a planner to run may be exponential in

Foundations

Before discussing motion planning algorithms, we establish concepts used in many of them: configuration space obstacles, collision detection, graphs, and graph search.

Configuration Space Obstacles

Determining whether a robot at a configuration

The explicit mathematical representation of a C-obstacle can be exceedingly complex, and for that reason C-obstacles are rarely represented exactly. Despite this, the concept of C-obstacles is very important for understanding motion planning algorithms. The ideas are best illustrated by examples.

A 2R Planar Arm

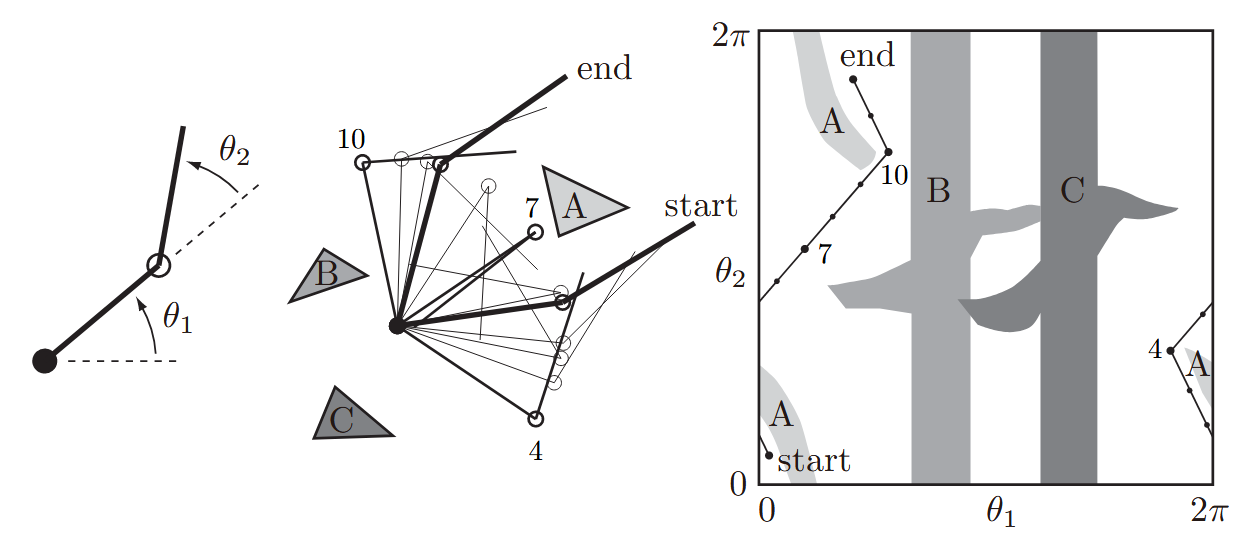

(Left) The joint angles of a 2R robot arm. (Middle) The arm navigating among obstacles A, B, and C. (Right) The same motion in C-space. Three intermediate points, 4, 7, and 10, along the path are labeled. (Lynch & Park, 2017).

The figure above shows a 2R planar robot arm, with configuration

The C-space on the right in the figure shows the workspace obstacles A, B, and C represented as C-obstacles. Any configuration lying inside a C-obstacle corresponds to penetration of the obstacle by the robot arm in the workspace. A free path for the robot arm from one configuration to another is shown in both the workspace and C-space. The path and obstacles illustrate the topology of the C-space. Note that the obstacles break

A Circular Planar Mobile Robot

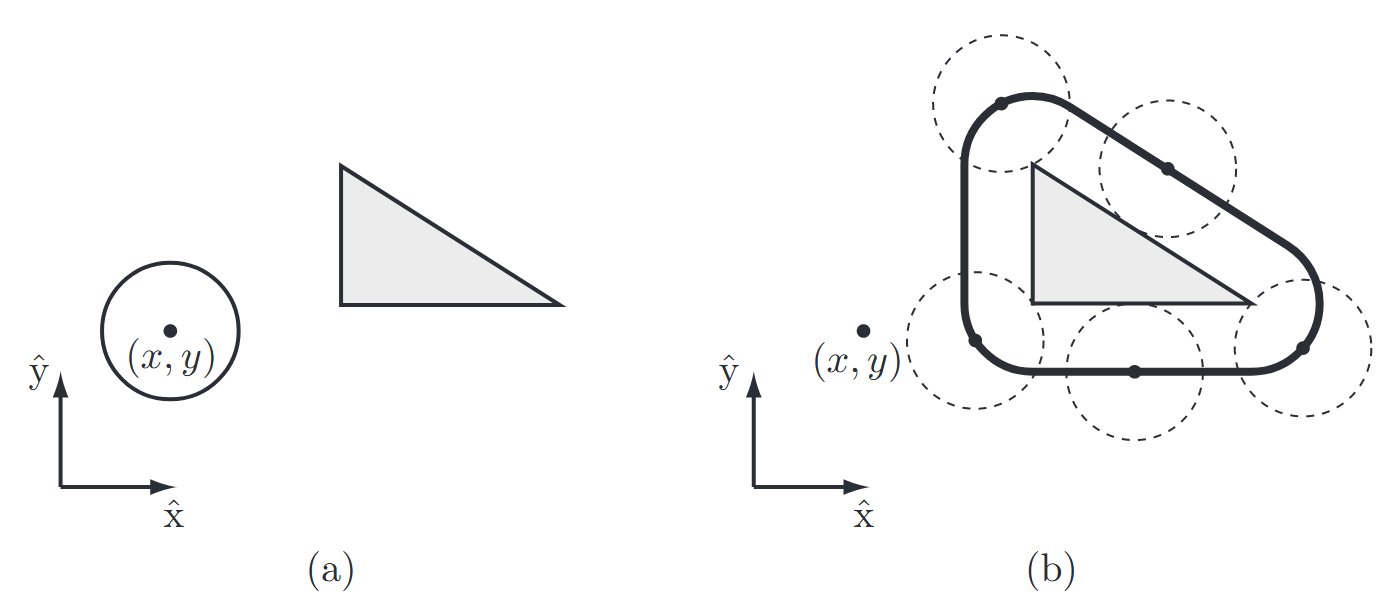

(a) A circular mobile robot (open circle) and a workspace obstacle (gray triangle). The configuration of the robot is represented by

, the center of the robot. (b) In the C-space, the obstacle is “grown” by the radius of the robot and the robot is treated as a point. Any configuration outside the bold line is collision-free. (Lynch & Park, 2017).

The figure above shows a top view of a circular mobile robot whose configuration is given by the location of its center,

The “grown” C-space obstacles corresponding to two workspace obstacles and a circular mobile robot. The overlapping boundaries mean that the robot cannot move between the two obstacles. (Lynch & Park, 2017).

The figure above shows the workspace and C-space for two obstacles, indicating that in this case the mobile robot cannot pass between the two obstacles.

Exercises

Question 1

The given manipulator is at rest at

that will cause the manipulator to arrive at its final angle with zero angular velocity.

Solution:

This is a motion planning problem in the joint space.

Joint value constraints are given at initial and final points:

Since there are

Given constraints:

Derivative of the polynomial:

Applying the constraints:

Applying

Applying

For

Applying

Solving the system of equations:

From equations 3 and 4:

Solving:

Final polynomial:

Results Analysis:

Manipulator Angular Velocity:

- Starts and ends at zero as required

- Has intermediate velocity changes

Manipulator Angular Acceleration:

Note:

The planned path requires non-smooth angular acceleration at the start and finish, which will require (infinitely) high motor torques! Conclusion: Add constraints for accelerations in practical applications.

Conclusion: Joint Space Planning

When to use: Plan a path in joint space when the gripper’s motion is simple or unimportant.

Pros:

- No danger of reaching singular points

- The gripper’s position can be computed directly using forward kinematics

Cons:

- Hard to generate a meaningful path for the gripper

Question 2

Compute a piecewise linear path for the gripper between the points:

Initial point:

Final point:

Starting and ending with zero velocity and acceleration, given that

The given manipulator.

Solution:

Since the path planning is in Cartesian space, we must first compute the gripper workspace and ensure any planned path is within it.

Workspace Analysis:

The workspace is determined by the manipulator’s geometric constraints, showing the reachable area for the gripper.

The gripper’s workspace.

Piecewise Linear Path:

Since we cannot move the gripper along a single linear segment between the two points, we add an intermediate point

The path consists of two segments:

- From

- From

The gripper’s path. (green) Path with intermediate point. (red) Linear segment.

For each linear segment, we have six requirements for each coordinate:

Position constraints:

Velocity constraints:

Acceleration constraints:

With

For each segment, we plan

Segment Planning:

First segment:

- Start:

- Time:

- Functions:

Second segment:

- Start:

- Time:

- Functions:

Complete path:

We control the manipulator’s joints through motors. To find the joint values, velocities, and accelerations that cause the gripper to move along the designed path:

Joint Values (Inverse Kinematics):

The joint values are computed by solving inverse kinematics, solved in a previous tutorial:

Joint Velocities and Accelerations:

Using the linear Jacobian matrix:

Joint velocities:

Joint accelerations:

Jacobian inverse:

Velocity calculation:

where

Conclusions: Cartesian Space Planning

When to use: Plan a path in Cartesian space when the gripper’s motion is important.

Pros:

- Easy to visualize the gripper’s path

- Easy to avoid obstacles in the workspace

Cons:

- Requires drawing the gripper workspace

- Requires translation to joint values using inverse kinematics