Contact Kinematics

Let us begin with a mathematical representation of rigid-body contact. Let

That is, the minimum distance between pairs of material points of the two bodies. It can be proven that for

Figure 3.1: Examples of distances between rigid bodies.

If the positions and orientations of

Constrained motion that maintains constant distance between bodies satisfies

so that

Time-differentiation gives

Using

This holds also for the limiting case of contact

In most cases, the contact is unilateral, so that for

Note:

This is a sign convention statement. Since

points from to , a positive relative normal velocity means the gap is opening (separation), and a negative one means the gap is closing (impact/penetration tendency).

The fact that

No-slip contact (or pure rolling) is where

Note:

“No slip” means both the normal component and the tangential component of the relative velocity vanish. So pure rolling is stronger than “maintaining contact”, which only enforces the normal component to vanish.

Note that this does not necessarily imply that the contact points

Question: Is the no-slip constraint integrable? That is, can it be replaced by a holonomic constraint?

In order to answer this question, we need to consider and prove the following statement:

In pure rolling motion, the trajectories that the contact pointsmake on the boundaries of the bodies and have equal arc lengths. Proof:

Consider two body-fixed reference frames,attached to and attached to . Let and denote angular velocity vectors of the two reference frames. Let be body-fixed points on the bodies that are instantaneously in contact at time . Let denote the location of the contact point, which moves on the boundaries of the bodies and coincides with both and at time . We can calculate velocities using differential operator’s rule as: Since both

and are body-fixed points, the frame derivative terms vanish, i.e. . At time , the relative velocity at the contact point vanishes, giving: Velocity of the moving contact point

can also be derived using differential operator’s rule in and as: At time

the points coincide, so and . Substituting this and (3.2) into (3.3) gives: The equated terms in (3.4) are the velocities of the contact point

as measured by observers attached to the two body-fixed frames and . Note that (3.4) holds for each time . The arc lengths of the two paths that

travels on the boundaries of and are obtained as: From (3.4) we conclude that:

Note that the boundary of a 3D body is a two-dimensional surface, whereas the boundary of a 2D body is a one dimensional curve, that can be parametrized by its arclength

. So, is the no-slip constraint integrable?

In 2D motion, yes. The constraint

can be written as . Together with the contact constraint it reduces the number of DOFs for the relative motion to . For example, for a wheel rolling on the ground in 2D,

. The contact constraint is , and the pure rolling constraint is . Integrating gives . The motion has 1 DOF and can be parameterized by or by . Examples: wheel on ground (the wheel’s rotation angle directly determines horizontal position), planetary gear (constrained rolling in a gear train). For smooth bodies in 3D no-slip constraints are NOT integrable. Examples: upright rolling disc on plane, rolling sphere, rolling ellipsoid.

For a body with a non-smooth boundary in contact with a smooth body, a vertex point of

will keep contact with a fixed point on the smooth body . In such a case, rolling is integrable also for 3D motion. Example: Euler’s spinning top.

Statics of Contact Forces and Friction

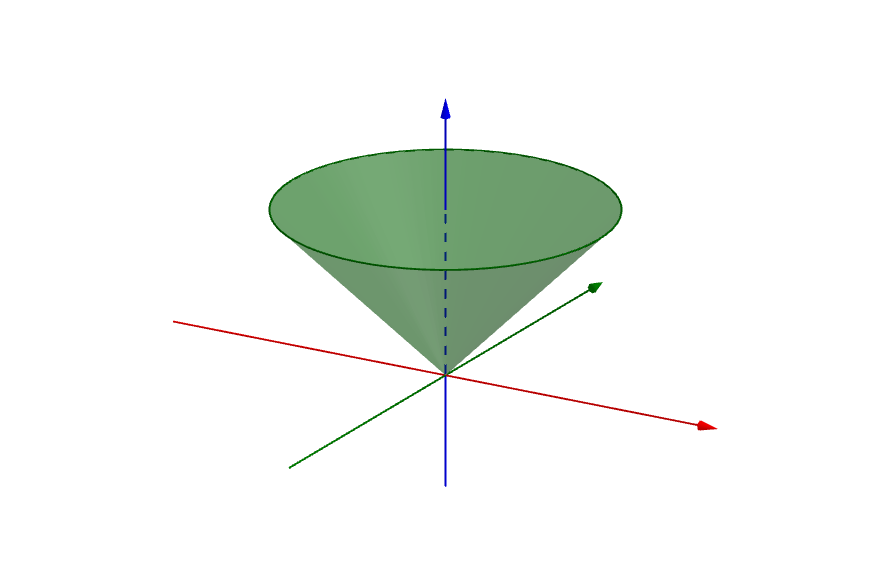

Consider two rigid bodies in 2D, having a point contact. We can (uniquely) define the unit vectors

Figure 3.2: Contact forces.

When the contact is subject to compression load in normal direction, the bodies undergo small elastic deformations. Assuming that the bodies have large but finite stiffness, these deformations are localized near the contact area, and one can still consider the nominal undeformed shape of the two bodies, with small local penetration in normal direction:

Figure 3.3: Contact forces with penetration.

For small deformations, the normal force

Now, suppose that after applying a normal loading force

Figure 3.4: Loading force in tangential direction.

In the limit of rigid bodies, the whole segment of micro-slip motion is lumped to zero, and one can replace the tangential displacement

Figure 3.5: Coulomb’s friction law.

The graphic description of this friction law states that the direction of friction force

called friction angle. A simple experiment for determining the friction coefficient is to put the body on an inclined plane and gradually increase the slope until reaching a critical angle

Figure 3.6: Friction cone, friction angle.

After macro-scale slip begins, the actual friction force

To summarize, the friction law in a unilateral contact can be formulated as:

Figure 3.7: Static friction force of unilateral contact

For simplicity, in many cases one does not distinguish between static and dynamic friction and assumes that

Figure 3.8: Viscous damping and Stribeck’s effect.

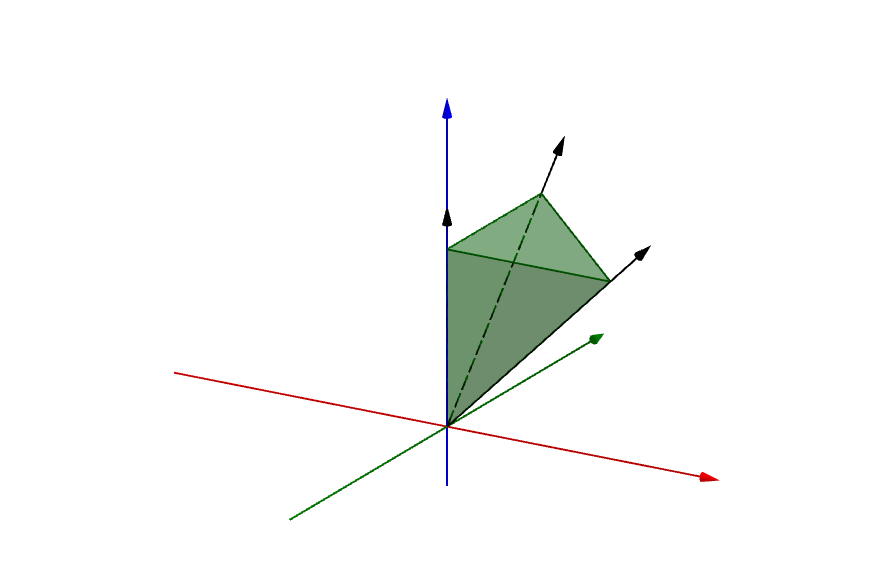

Extension of Coulomb’s Friction to 3D

The tangent is now a 2D plane, perpendicular to

Coulomb’s inequality states that

Figure 3.9: 3D frictional contact.

Another effect that may exist in 3D frictional contact: If the contacting bodies slightly deform to a contact region of small circular patch, tangential forces may generate added resisting “torsional moment”

Graphical Analysis of Force Statics in 2D

When a static body/structure is subject to two external forces (vectors) and no external torques (i.e. two-force member), the forces are equal and opposite, and must be directed along the line connecting the two points where the forces act.

In the case of three external forces and no external pure torques, the lines of action of the three forces must intersect at a common point, OR all three forces must be parallel and anti-parallel (this is actually a limit of the general case with intersection point approaching infinity).

Figure 3.10: Three-force equilibrium.

Observe the following rigid object supported by two given frictionless point contacts (

Figure 3.11: 2D force statics.

Gravity acts at the body’s center-of-mass

What if we do have frictional contacts? What if instead of gravity, we’d like to know whether the contacts can support some general force?

Figure 3.12: General 2D force statics problem.

To answer these, we’ll learn about two methods: Linear Programming and Moment Labeling. But first, we need to understand Polyhedral Cones.

Polyhedral Cones

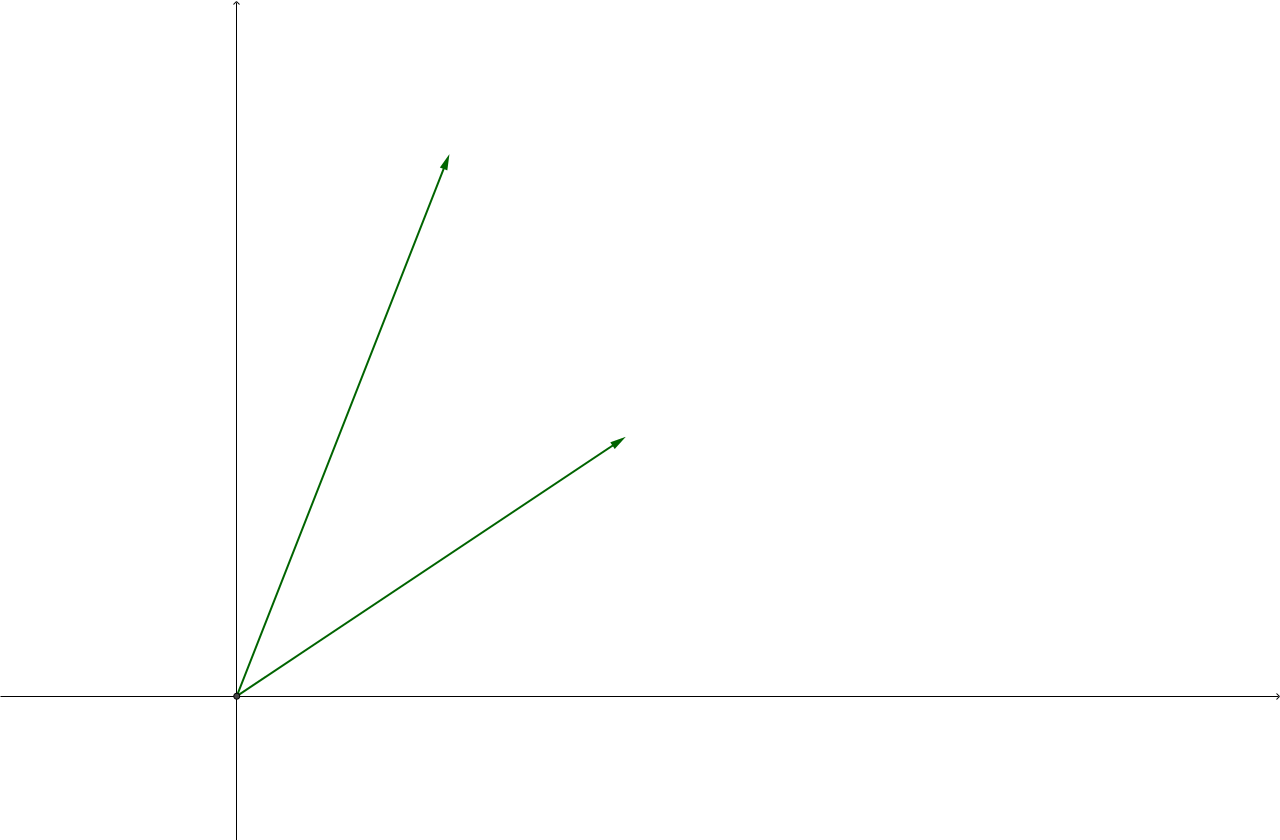

A vector

Where

The “normalized” vector

Note:

A wrench packages “force + where it acts” into a single vector. In 2D, once you know the force direction and its moment about a reference point, you have effectively described the force’s line of action.

Claim: every load of total force and torque in 2D is equivalent to a single force + line of action. The only exception is pure torque with zero total force, which is a limit case where the action line goes to infinity. 3D analogue of this claim is that every load of total force and torque in 3D is equivalent to a single force + line of action + torque about the line of action. This is the origin of the term “wrench”. Similarly, any rigid-body motion in 3D is equivalent to pure translation about a spatial line + rotation about the same line. This motion is called a “screw”, and 3D rigid-body velocity or infinitesimal motion is called a “twist”.

In many cases, the force is unidirectional as in unilateral contact which supports only compression forces

We now state that the

Definition:

A set

is a cone if for any we have for any scalar . That is, is invariant under positive scaling. Note that contains the origin by definition.

Definition:

A set

is convex if for any we have for any scalar . That is, the straight line segment connecting and is entirely contained in .

Corollary:

A set

is a convex cone if for any we have for any scalars .

Figure 3.13: Convex cone that is not a conic hull of finitely many generators. (Wikipedia).

Figure 3.14: Convex cone generated by the conic combination of the three black vectors. (Wikipedia).

Figure 3.15: A cone (the union of two rays) that is not a convex cone. (Wikipedia).

More specifically, a convex cone of the form (3.7) is called a polyhedral convex cone (PCC): it can be constructed from non-negative combinations of a finite set of generators.

Theorem:

Any polyhedral convex cone from (3.7) can be defined using an equivalent form:

Where

is a constant matrix of dimensions whose rows are the contact vectors .

Interpretation: Intersection of

Definition:

A convex polyhedral set (CPS) is defined as:

Note that (3.8) is a special case of (3.9) but not vice versa, since

The Moment Labeling Method

This is a method for graphical representation of polyhedral convex cones of wrenches spanned by action lines of unilateral forces in 2D. Consider a PCC defined as in (3.7). We now define two sets of points in the 2D plane as:

We arbitrarily define that positive torque is counterclockwise (CCW). Graphically, this means that:

For example, if

Figure 3.16: The sets

.

Now we show how one can construct the sets

Theorem:

The fundamental theorem of moment labeling method says:

Thus, if the wrench set

Now,

The set of loads that can be resisted/balanced by wrenches in

Note:

The analysis only guarantees that a static equilibrium solution exists. It does not tell us whether it will actually happen. The equilibrium may not be stable, for example.

Example:

Given the following body with two frictionless unilateral contacts, find all the loads that can be resisted.

Figure 3.17: A body with two frictionless unilateral contacts.

Solution:

First, we assignand to each side of each action line. That is, the and for each :

Figure 3.18:

and assignment for each . Now we can construct the general

and for the system simply as the intersection as described in (3.13):

Figure 3.19:

and of the whole system. We know all directed force lines that can be resisted are such that the entire set

lies at the right side of the line while the entire set of lies at the left side of the line.

Figure 3.20: All force lines that can be resisted by the frictionless unilateral contacts.

Example:

Given the following trapezoidal object with two frictional unilateral contacts, determine whether the object can be lifted under gravity.

Figure 3.21: A body with frictional unilateral contacts.

Solution:

Figure 3.22:

and assignment for each .

Figure 3.23:

and of the whole system. From the figure above we can see that the only force lines which can be resisted are upwards forces (remember,

must lie to the left of the line, and must lie to right of the line). Therefore, gravity won’t be resisted by the contact forces, no matter how strong the grip is on the object. But, if the friction cones are larger, we get that

:

Figure 3.24: A case of large friction cones.

Now, any line has

to its “right” and to its “left”. Therefore, any load can be resisted by the contact points, including gravity.

Theorem:

A 2D grasp with two frictional contacts satisfies force closure iff the line segment connecting the two contacts is fully contained in the two friction cones.

Undesired effect of force closure is jamming/wedging/clamping/self-locking (Hebrew: כליבה). Examples: stuck drawer, jamming in peg-in-hole insertion.

Figure 3.25: Example of jamming.

Representing Planar Statics Problems with Unilateral Frictional Contacts as Convex Polyhedral Sets

A unilateral frictional contact force in 2D satisfies Coulomb’s law

On the other hand,

The wrenches

Figure 3.26: No-slip and slipping contact.

Example:

We are given heavy bar on two moving supports with friction. It is prescribed to a slow relative motion of its supports (quasistatic motion).

Figure 3.27: Heavy bar on two moving supports with friction.

- Which contact(s) is slipping?

- Is it possible that both are sticking? No. Kinematically infeasible, relative distance is changing.

- Is it possible that both are slipping? No, except for specific location of center of mass. Statics is under-determinate.

Let’s apply moment labeling. assuming that both contact slip, we know that direction of the two contact forces, one two opposing edges of friction cones. Moment labeling implies that COM must lie on the vertical line passing through the intersection point of the force lines - too specific.

Figure 3.28: Bar on moving supports - assuming both contacts slip.

Now assume one contact slips and the other sticks. Which COM loads can be resisted by the contacts?

Figure 3.29: Bar on moving supports - assuming one contact slips and the other sticks.

Figure 3.30:

and of slip-stick configuration. The contact which is closer to COM (in horizontal distance) is sticking, while the other one is slipping. Same happens when supports that are moving away from each other. For supports that are moving away from each other, the farther contact from COM will keep slipping. For supports that are moving towards each other, the two contacts alternate between stick and slip.

The bipedal crawling locomotion example - periodically varying distance between two feet with passive frictional contacts. Manipulating COM location can dictate the stick-slip motion of contacts to induce net propulsion of inchworm-like crawling.

Linear Programming

The moment labeling method provides geometric intuition, but for computational analysis of contact forces, we can formulate the problem as a Linear Programming problem.

The linear programming problem (LP) is a constrained minimization problem with objective function and inequality constraints which are both linear (polyhedral) in variables. It is defined as:

For

Figure 3.31: Visualization of the constraints

.

The value to minimize (the cost function) will be of the form:

In linear programming, because the gradient

The Fundamental Theorem of Linear Programming

If the minimum/maximum solution of (LP) exists, then it is attained at a vertex point of the polyhedral set defined by (3.9). For

The theorem enables solving the optimization by reducing our search of

There are two typical cases when a solution the the LP problem does not exist:

- Infeasible case - when the set

- Unbounded case - the minimum is

Generalization of the LP Problem

- Find a maximum instead of a minimum: equivalent to original problem since

- Adding